On March 15, 2016 after a devastating primary loss in his home state of Florida, Marco Rubio suspended his campaign. He won only one county, Miami-Dade. He was utterly bested by Donald Trump. His loss could very well mark the end of his career. He will lose his seat in the senate and the Florida primary revealed his limited electability at the state level. His defeat and subsequent retreat doesn’t mean he should be forgotten. Rubio, more than any other figure in the Republican Party, explains how the GOP understands the Latino community. Rubio was not a happenstance shooting-star, the wish of a wayward party come to life. His rise was certainly meteoric but this meant that he was destined for a crash-course and an eventual burn-out. His rise was always connected to his fall. Rubio’s place in the Republican Party was predicated on the fundamental misunderstandings of the Latino community by the party itself.

After two presidential defeats in 2008 and 2012, the Republican National Committee, at the urging of committee chairman Reince Priebus, put together a report on growth and opportunity. They pinpointed their present problem and future prospects: young people and minority communities. “Young voters are increasingly rolling their eyes at what the Party represents, and many minorities wrongly think that Republicans do not like them or want them in the country. When someone rolls their eyes at us, they are not likely to open their ears to us,” the report disclosed. Party leaders had to tell their rank-and-file members that in the 21st century, “America looks different.” The population that elected Reagan was not the same that elected Obama—in 1980 the electorate was 88% white, in 2012 only 72%. The report identified the key community of color that Republicans needed to win: Latinos. In 2050, Latinos would comprise 29% of the electorate. Republicans knew very little about Latinos but what they did know was that there were a lot of them.

In the “Growth and Opportunity Report,” the committee dedicated an entire section to the Latino population. Republicans had failed in reaching out to this key community. If they wanted to persuade the Latino community to join the GOP, they needed more than anything to “embrace and champion” comprehensive immigration reform. They reasoned that immigration reform was not a refutation of Republican values, but an extension of them. “Comprehensive immigration reform is consistent with Republican economic policies that promote job growth and opportunity for all” read the report.

While the party had alienated Latino voters, not all hope was lost. Latinos could still be reached. It would just require a change in marketing. Using the language of advertising, the report reasoned that the Republicans’ difficulties with Latinos was not a problem of a faulty product—Republican policies—or brand—Republican ideas—but a problem of messaging. “Message matters. Too often Republican elected officials spoke about issues important to the Hispanic community using a tone that undermined the GOP brand within Hispanic community,” the report explained. Republicans needed to change their tone and their slogans so they wouldn’t offend Latinos. It was the words they had used, not the policies they had offered that had turned-off Latinos.

After changing the words they used, Republicans needed to change the face of the party. In the surveys commissioned for the 2012 report, it was discovered that many voters considered the GOP to be a party of “scary,” “narrow minded,” “out of touch, “stuffy old men.” The RNC proposed nationwide “listening sessions” where minority communities and Latinos could voice their concerns and be heard by Republican politicians. They urged the party to institutionalize minority recruitment and promotion within the party. The GOP needed to train and retain “ethnic conservatives” to be used strategically in key demographic markets. These “ethnic conservatives” could reach out to African-American, Mexican-American, Indian-American communities in their own languages and with a cultural familiarity. The chasm between Latinos and the Republican Party, then, could be bridged with friendly words and welcoming smiles.

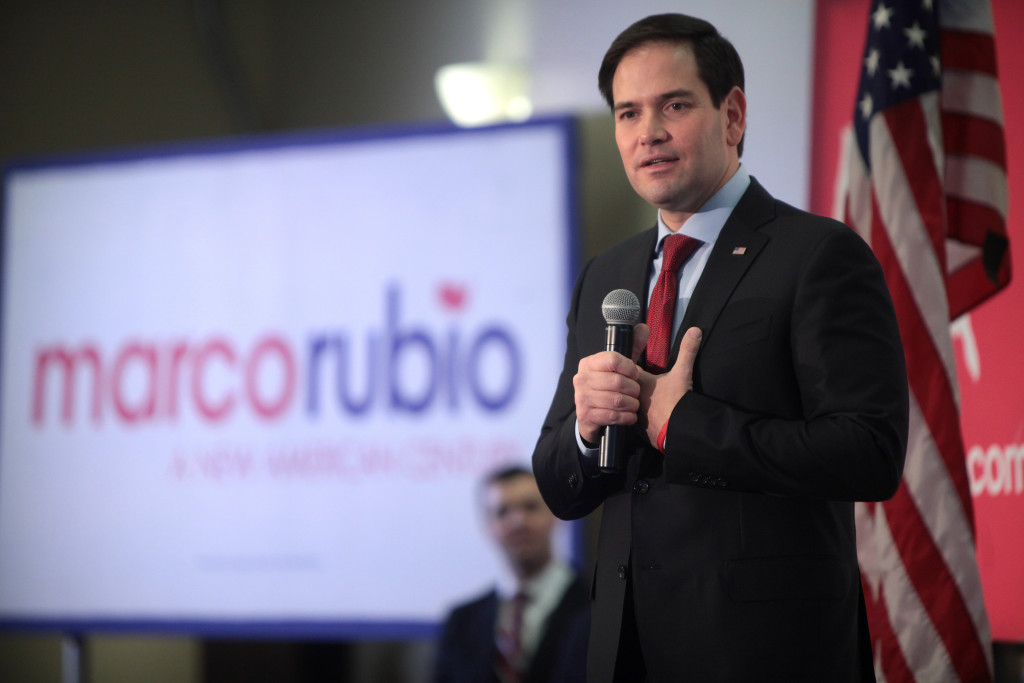

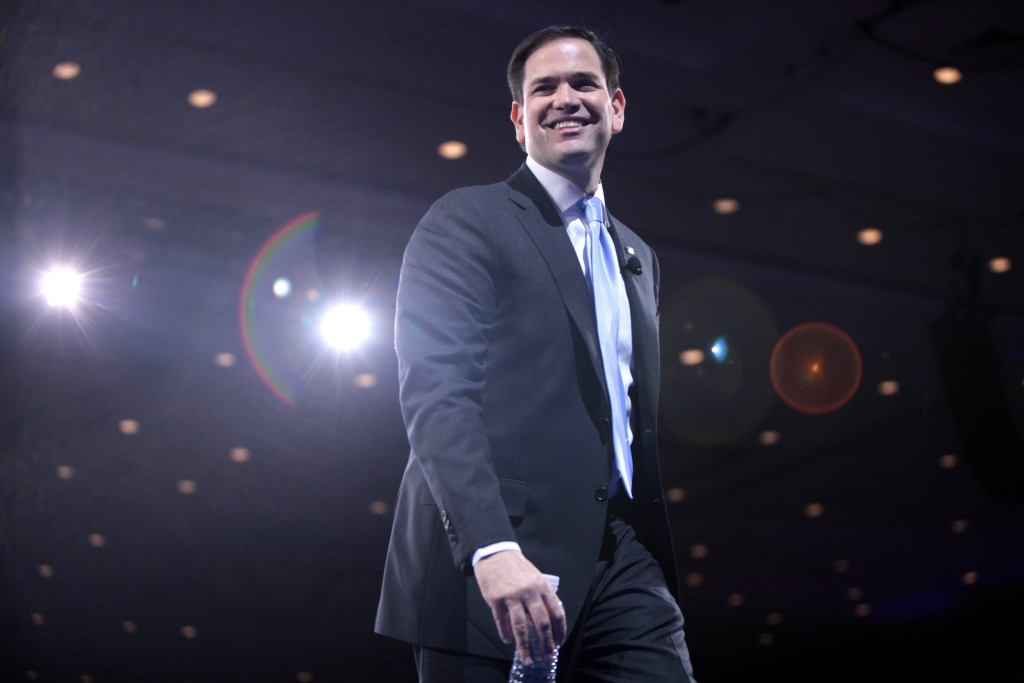

So it seemed that the emergence of Marco Rubio was the answer to the Republican’s problem. He was the model “ethnic conservative” that the 2012 report had identified: young, attractive, bilingual, a family man, a former college football player who married a cheerleader and had beautiful children. Rubio had an inspiring immigrant tale. The Rubios fled oppressive government overreach to come to the U.S., the land of the free. Marco appreciative of the opportunities of liberty and freedom, made good on the promises of the nation, and ran for president. He was the Republican answer to Obama. Rubio, as the title of his memoir suggested, was an American son with American dreams, not the dreams of a Kenyan father.

Rubio had even championed immigration reform in 2013. He was part of the “Gang of Eight,” a bipartisan group composed of four Democratic and four Republican senators that tried to tackle the issue. The “Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act” provided a path to citizenship, increased border security, created a guest-worker program, and increased the amount of H-1B visas for skilled workers. The bill passed the senate and then died in the house.

His presidential announcement in 2015 used the message that the RNC’s “Growth and Opportunity Report,” hoped the party would adopt. He declared in front of Miami’s Freedom Tower that his immigrant family was just one in the “larger story of the American miracle.” E Pluribus Unum was not a dead expression, but an apt explanation of American history: “united by a common faith in their God given right to go as far as their talent and work would take them, a collection of immigrants and exiles, former slaves and refugees, became one people, and together built the freest and most prosperous nation ever.” He embodied the promises of the past century and promised his presidency would establish a new American century.

Rubio began his campaign with an inspired American poetry that pulled from Whitman, Algers, and Reagan. Unfortunately, his soaring campaign poetry devolved into a sad prose before he could even govern. Governor Chris Christie attacked Rubio for his robotic repetition of the same phrase multiple times in one debate—namely, that President Obama knew exactly what he was doing to the nation. After being perceived as the best alternative to Donald Trump, Rubio then attacked Trump. His attacks too devolved sadly. Rubio began using sophomoric antics to undermine Trump, allusions to the size of his hands being the worst. His juvenile attack strategy did not work and he lost the support of some voters. Eventually, Rubio apologized for his words, claiming that it embarrassed his children.

Rubio was supposed to be the Republican’s answer to their problems. He was young, Latino, bilingual, and used an inspirational message of immigrant assimilation that was supposed to appeal to a wide base. Yet, he fell flat. Why?

Republicans in their 2012 report and subsequent strategy overestimated the willingness of their base to accept minorities and misunderstood the Latino community.

After years of dog-whistle politics, their own electorate turned against them. While Romney offered self-deportation as a solution to unauthorized migration in 2012, Donald Trump offered forced deportation in 2015. As far as the Republican base was concerned, self-deportation wasn’t enough. Trump’s border wall and his plan for removal were the correct answers. Anti-Mexican, anti-immigrant rhetoric wasn’t new. In the 1990s, California’s Proposition 187 tried to deny unauthorized migrants basic services and English-only proposals flourished across the nation in response to the growing Latino population. By the early 2000s, the Minutemen encouraged gun-wielding and binocular-sporting whites from across the nation to come secure the border—it was their patriotic duty, as the title of their organization suggested. The Minutemen’s rhetoric continued in the form of the Tea Party. The Tea Party won local and state elections across the country on anti-immigrant rhetoric, even though they were hundreds of miles from the border. Kansas Republican state representative Virgil Peck believed the solution to unauthorized migration was shooting Mexicans like feral hogs from helicopters along the border. Republican Congressman Steve King claimed that Mexicans had “calves the size of cantaloupes” because they were hauling large amounts of drugs across the desert. Politicians made names for themselves by demonizing Latinos. Republican voters were misinformed about Latinos, but it was because of the Republicans’ own misinformation.

The Republican plan to draw Latinos into the party through politicians like also Rubio failed because they misunderstood Latinos. The report made clear that all Republicans needed to do to win over Latino voters was to enact immigration reform. Republicans understood Latinos only as an immigrant community. Of the 27.3 million Latino voters in the U.S. nearly half of them are young and native-born. They are not immigrants, although many of them have a family connection to immigration. They are increasingly educated, nearly half of the voters have at least some college credit. In fact, education is the top issue of concern for Latino voters, followed by the economy, healthcare, and then immigration.

While Republicans have for decades accused Democrats and liberals of playing “identity politics,” it turns out that Republicans have played a particular type of crass and divisive white identity politics on the national and presidential level since the Nixon administration’s “Southern strategy.” The politics of white supremacy continue with Trump and policies of white privilege continued with Carson, Rubio, and Cruz. Building on white racial normativity, Republicans have turned identity politics into an ideological bogeyman, a contrived type of politics based on certain identities—race, gender, sexual orientation—that superseded national identities and obliged its members to a particular radical anti-American agenda. Identity politics were a zero-sum game where minority benefits came at the expense or punishment of whites. Recently, Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan repeated this idea in a response regarding his “State of American Politics” speech on March 23, 2016. He said:

What really bothers me the most about politics these days is this notion of identity politics. That we’re going to win election by dividing people. That we’re going to win by talking to people in ways that divide them and separate them from other people. Rather than inspiring people on our common humanity, on our common ideals, on our common culture, on things that should unify us.

It has been this fundamental misunderstanding of the politics of identity and how shared experiences of exclusion structure political identification that have led Republicans to failure. The 2012 and 2016 Republican presidential candidates have been diverse: Herman Cain, Michelle Bachman, Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, Rubio and Ted Cruz. Republicans have pointed out on multiple occasions that while the Democrats were supposed to be the party of minority voters, the GOP was the party of diversity. Of course, they used diversity in the insipid language of neoliberalism—a euphemism for people of color, not a social or political commitment to not only desegregation of white institutions but the systematic integration of them. For this reason, none of their “diverse” candidates won the support from the communities they were supposed to represent. Republicans believed that racial identity and the discrimination derived from it is superficial; it is only skin deep. They did not have to change their policies, just the color of the face or the gender of the person.

Rubio was supposed to be the solution to the Republican’s Latino problem, but he failed miserably because of the GOP’s own failure to understand the Latino community. Rubio could speak Spanish, but as we learned in an exchange he had with Cruz, he used his bilingualism to promote restrictive immigration policies. He disowned the “Gang of Eight” immigration bill. And all the while, his immigrant tale regurgitated 19th century tropes of European migration, instead of the 20th century privileges and realities of Cuban community in the U.S. Rubio’s family and the Cuban community were never considered “illegal” in the U.S. The 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act granted Cubans a protected refugee status and gave them a pathway to citizenship—a privilege extended to no other immigrant group in the United States. Rubio could be an American son following an American dream because his family was never at risk of deportation and he benefitted from the ability to attend college at in-state tuition rates—again, more privileges not extended to an increasing portion of the Latino community.

The 2012 Republican strategy to entice Latino voters focused only on a change in messaging. The Republican leadership believed it was the words that their members were using that hurt Latinos, not their policies. But, Latinos weren’t mad because Republicans weren’t listening to them or because they weren’t speaking Spanish. They were mad because Republican policies and electoral victories based American salvation on Latino demonization and exorcism. Rubio never challenged those assumption or policies, yet his presence challenged too many of his own party’s voters.

Leave a Reply