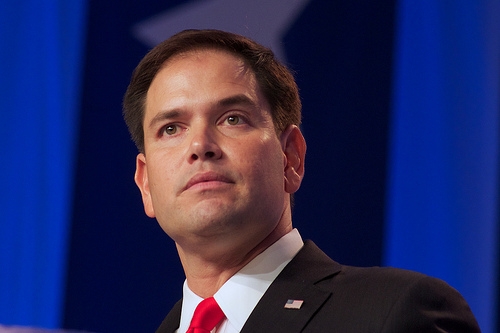

Republicans’ have a Latino problem. Their anti-Mexican rhetoric isn’t working out. Donald Trump has been dumped by NBC, UNIVISION, and Macy’s for his anti-Mexican statements. Their commentators haven’t helped much either. Some have indicated that this is due to Latinos growing economic and political influence. Nonetheless, the ever-growing Republican presidential field features the first two Latino presidential candidates in U.S. history, Texas senator Ted Cruz and Florida Senator Marco Rubio. Both are Cuban and both espouse a particular brand of American exceptionalism and anti-federal government policy solutions.

When they tell their families’ stories, however, they are not aimed at Latina/o families. Instead, their immigrant narrative is a repetition of an idealized nineteenth century story that does not fit into the late twentieth century context in which it unraveled. In their recounting, their families seem more like German or Italian families than the Cuban diaspora. Their families never passed by the Statue of Liberty or entered Ellis Island, but they came to the U.S. for the American dream, for the chance to succeed and experience a type of freedom unequaled anywhere in the world. At first their families were poor, oppressed, and downtrodden but they worked hard and sacrificed. Then, they succeeded—both economically and in assimilating. The only particularity of the Cuban experience that Cruz and Rubio mention is that their families fled communism. For them, communism—of which American liberalism is just a step away, brought closer by Obama’s near Marxism—is any form of government intervention. Big government, whether Castro’s communism or Roosevelt’s New Deal—robbed their families of opportunity, oppressed their communities, and sapped individual initiative. Their families and community witnessed the horrors of government run amok and that’s why they don’t want to see it in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave. That’s why they are anti-liberal crusaders—they’ve seen the destruction that liberalism can bring.

These stories give the false impression that individual action alone leads to attainment. Their families, set free by the free market, worked harder and sacrificed more than any other families and that was the reason they succeeded. Certainly, Los Rubio and Los Cruz, worked hard, but their sons fail to recognize the incredibly important privilege that their Cuban families had in the form of government policy. More than immigrants, the Cuban community has been recognized as refugees in the U.S. since 1959. Their story is not rooted in the economic transformations brought by the long industrial revolution of the nineteenth century that moved populations and capital across the world. It is not in the even longer history of continental colonization that brought Spaniards and ethnic Mexicans to North America. The Cuban story is really a product U.S. Cold War policy. (Although, there was a small presence of Cubans in the U.S. in the late nineteenth century, including Cuban independence activist and poet, José Martí.)

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, the first sizable population of Cuban immigrants came to the United States, concentrated in Florida but also parts of New York. This group tended to come from the middle and upper classes. They were educated and brought with them substantial capital. They were fleeing the redistributive policies taking place in Cuba. Many of these families had a familiarity with the U.S. Before the revolution, Cuba had a long history with the U.S. After the Spanish-American War, Cuba was an actual colony of the U.S. After its independence, Cuba was practically an American colony, economically dependent on the U.S. through sugar exports and American tourism. The Cuban elite benefitted from this close relationship, sending their children to prestigious American universities and keeping their money in American banks. During the Cold War, the U.S. confused the anti-colonial nationalism arising across the Third-World for communism. The U.S. saw in the Castro led revolution the specter of communism, which they feared was spreading across the world. Between 1959 and 1963, over 200,000 Cubans came to the U.S., most were economically and socially affluent. Nearly 40 percent of this group had college educations, while only 4 percent of the Cuban population in general had high school diplomas. They brought with them capital and business connections and turned Miami into a central point in Latin American business. The first groups of Cuban immigrants were not weak and weary masses yearning to be free.

In addition to their economic affluence, Cubans benefitted from the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA). This act stated that any Cuban to reach the U.S. after 1959 who had been in the country for at least one year would be given a visa, would be eligible for permanent residence, and, eventually, citizenship. The CAA recognized Cubans as refugees and not immigrants. It gave Cubans a pathway to citizenship. In addition, the CAA provided and continues to provide financial assistance from the federal government in the form of public assistance, Medicaid, food stamps, English courses, and scholarships. Florida provided direct cash payments to Cuban families. Cubans both then and now have access to special business and start-up loans. The protections of the CAA give Cubans unequaled access and opportunities in the U.S. No other group of Latinas/os or migrants receives these same benefits. The second wave of Cuban migrants that came in 1980s benefitted from these policies. The 1980 Mariel boatlift, brought 125,000 more Cubans to South Florida alone. The “boat people” of the ‘80s and ‘90s were not labeled or considered “illegal immigrants.” If they touched land, they were recognized as refugees and given a pathway to citizenship and automatically awarded permanent residence status.

The treatment of Cubans was remarkably different from the treatment of other Latina/o groups during the same time. During the 1930s, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were deported during the Great Depression. When WWII brought a labor shortage, the U.S. imported hundreds of thousands of Mexican workers to work in American fields and factories. By 1954, the government feared the wave of “illegals” entering the country and started Operation Wetback, an attempt to deport “illegal” Mexican workers. In addition, the racist immigration quotas that were established in 1924 to exclude non-white immigrants were not done away with until 1964. During the 1980s, while Cubans benefitted from the wet foot/dry foot policy, Central Americans who fled brutal military dictatorships that killed tens of thousands in the countryside of El Salvador and Guatemala, were not given the status of refugees because the U.S. supported the right-wing juntas. Central Americans were turned away and deported, many to their certain death. Churches and activists started an underground railroad of sorts called the Sanctuary Movement to help Central Americans fleeing the horrible conditions. Through the ‘90s, changes in border policy pushed migration flows out of Tijuana/San Diego and Juarez/El Paso into the Sonoran desert between Arizona and Sonora. This was intentional. Many officials believed that the terrain and conditions were so harsh that the threat of death would discourage migrants from trying to cross without authorization. Migrants still tried and at its peak in the early 2000s, on average one migrant died a day in the desert.

Today, Cubans are not illegal immigrants, but Mexicans are. While both groups leave without authorization from their home governments in many cases and step onto land “illegally,” one group is deported, policed, and interdicted while the other group is welcomed with a pathway to citizenship. Why? The answer is simple: government policy. Policies that push migrants to the economic and social fringes can be changed and those changes in policy can have long lasting impacts, as it did for the Cuban community. That lasting impact can be seen during the 1980s and even now. By the early 2000s, Cubans who arrived before 1980 had a 72 percent home ownership rate as opposed to only 47 percent of Latinas/os in general. Cubans have a higher household income than other Latina/o groups. 25 percent of Cubans age 25 and older have college degrees compared to only 12 percent of other Latinas/os. 28 percent of Cubans considered themselves Republicans, compared to just 15 percent of Mexicans. And, importantly for the Republican Party, the Republicans have two Cuban-American presidential candidates, while the Democrats do not have a single Latina/o presidential candidate.

While Cruz and Rubio are not the solutions to the nation’s problems, the protected and preferential treatment that their families and community received through immigration policy is certainly the solution to the Republicans’ Latina/o problem. Instead of calling Latina/o culture “deficient” or calling Mexicans “rapists” or calling government the problem and not the solution, perhaps the Republican Party should see how policies that benefit communities and give them access to the promises and potential of the nation create powerful, long-lasting political constituencies. This isn’t pandering. This is smart politics and good policy.

Great info, Aaron. I didn’t realize that Cubans had such a different (and more facilitated) experience immigrating to the U.S. than Mexicans.

Most Cubans, that came in the early 60’s were not allowed to bring money or belongings. Just a change of clothing and 10 cents to call home. Their property and money had already been seized. Only the smart ones that knew from the beginning of the Castro movement, knew to send their money to other countries before Fidel took power.