Despite dire warnings from the Republican National Committee, a slew of Republican presidential hopefuls have veered to the right and have alienated Latino voters. In an attempt to win an aging, isolated constituency that is increasingly afraid of technological, economic, social, and demographic change, the candidates have become enamored with the idea of overturning birthright citizenship in this country.

The lesser candidates have followed front-runner Donald Trump’s nativist and xenophobic rhetoric while Floridians Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush have shown moderation, which is not surprising given their family histories. Rubio is the son of Cuban exiles and Bush’s wife was a Mexican national, which would in a very real way make Rubio and Bush’s children—including George P. Bush, Commissioner of the Texas General Land Office—anchor babies themselves. Interestingly, Jeb Bush used the term anchor baby and in a testy exchange with reporters refused to concede that the term was offensive. He pushed the media to develop a better term but ultimately concluded that “I think that people born in this country ought to be American citizens.” Rubio answered Bush’s urging to develop a better term by calling them “human beings with stories” and not just statistics.

Not surprisingly, Trump has offered exaggerated incoherence and intolerance as a substitute for policy. On his presidential website, Trump’s only outlined policy position is his stance on immigration. In the ways that only Trump can, he confusedly connects two contradictions in his platform. He states that “America will only be great as long as America remains a nation of laws that lives according to the Constitution.” Then, a few lines down, he negates his reverence for the constitution by proposing a dramatic amendment to the constitution, ending birthright citizenship established in the Fourteenth Amendment. Apparently, Trump’s lone policy to “make America great again” is to end Mexican migration, build a wall, make Mexico pay for it, and deport Mexicans.

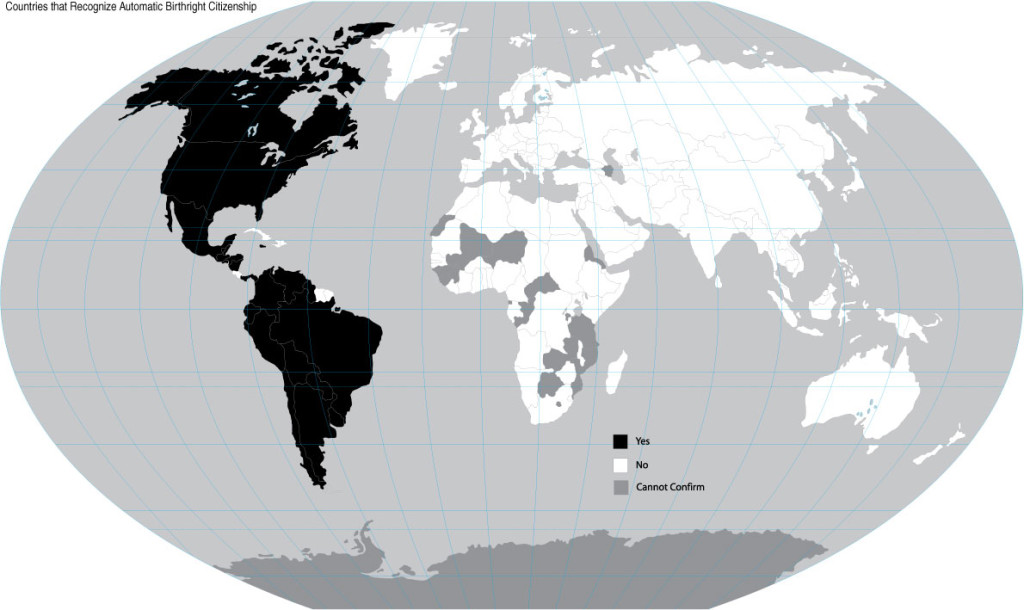

In addition to the rhetoric of Republican presidential hopefuls, the conservative Center for Immigration Studies released a map to show how few nations in the world award citizenship on the basis of birth alone.

Only among the nations of the western hemisphere is there near unanimity in the support of the idea of birthright citizenship. This is because it is a new world idea. Before mass migration to and colonization of the western hemisphere, people developed a sense of identity based on a geographic fixity that was generational. People lived, worked, and died on the same land for generations upon generations. Staying in one place allowed nations to develop national in-groups and out-groups. In the old world, these generational ties connected them and they also naturalized the inherent inequality of the monarchical system; the people were a family and the King was the father, his power and authority were natural and God-given. The peopling of the new world broke these ties that took generations to build. People had to develop new ways of creating the horizontal comradery necessary in forging nations and nationalisms. Enlightenment ideas and demographic reality allowed the new territories and the eventual republics of the new world to entertain and establish the notion of citizenship in their constitutions.

Although the inspired language of Enlightenment ideas hinted at expansive inclusion, this was not the case in the United States. At first, citizenship was extended to only white men. Women and racial minorities in the U.S. were excluded. In 1831, Native-Americans were excluded from citizenship. In the 1857 Dred Scott case the Supreme Court ruled that African-Americans, whether slave or free, were not citizens. It was not until after the Civil War that the Fourteenth Amendment returned citizenship to African-Americans and extended it to all people born in the nation, although the privileges that citizenship should have entailed were limited to all but white men. Then in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act and barred Chinese immigration for ten years and prohibited them from becoming citizens. Women’s citizenship was derivative and dependent on their husbands until 1922. Before then, if an American woman married a foreigner, she lost her U.S. citizenship and was given her husband’s. Citizenship would become increasingly important in the twentieth century, as the innateness of natural rights declined. In 1954, the Supreme Court would reason that citizenship is the right to have rights.

Even with all of its shortcomings and intentional exclusions, birthright citizenship created today’s generation of Americans. The nation was able to grow at the astounding rates it did during the nineteenth century because immigrants provided not only the labor for the industrial revolutions, but the resistance to laissez-faire capitalism and its excesses. In the mid-nineteenth century, German and Irish immigrants came by the millions. By the 1880s and 1890s, millions of Southern and Eastern European immigrants arrived in the United States. By 1890, fifteen percent of the U.S. population was foreign born. (In the 2010 Census, 12.9 percent of the population was foreign born.) These European immigrants tended to congregate in industrialized Northeastern and Midwestern cities. In 1900, 4/5 of Chicago’s population was foreign born or of foreign born parentage, as was 2/3 of Boston’s, and 1/2 of Philadelphia’s population. By 1880 there were nearly 100,000 Chinese immigrants in the American West and millions of Mexican migrants were entering the United States, many of them recruited in Mexico by American companies. Between 1920 and 1930, there was a 103.1 percent increase in the ethnic Mexican population in the U.S. By the twentieth century many of the sons and daughters of these immigrants considered themselves American. In the coming decades, various groups would demand the rights and respect that their citizenship entailed.

While many recognize their immigrant origins today, they reason away the obvious xenophobia and nativism of the current political moment by arguing that their ancestors came to the U.S. legally. For that very reason, they believe they are not anchor babies. However, it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the notion of “illegal immigration” existed. Prior to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, there was no such thing as illegal immigrants. It was during the period from 1882 and 1924 that the legal, political, and social formulations of illegal immigration developed. The impetus for these restrictive policies was eugenicist ideas that reasoned that non-white races were inferior to the white race. Non-whites needed to be kept out. This is why when many Americans say that their ancestors “came legally” it is only a half-truth and part of a more complicated history. Since the idea was developed, only non-whites could be “illegal.” The legacy of ideas that believed non-white people and cultures to be inferior continue today. If they didn’t why else would we need paramilitary forces whose only responsibility is to police and interdict non-white migrants?

Citizenship based on parentage or blood revives dangerous eugenicist concepts and excludes generations of future U.S. citizens on the basis of our past and present prejudices. Nativity is an ahistorical illusion. To base political inclusion and participation on an illusory genealogy is to prematurely foreclose on the nation’s future.

Birthright citizenship is central to the American idea. It is an idea that believes that the whole of the world can be one. It is an idea that we as a nation have not lived up to then and now. If we want to keep on pretending that the United States is a “nation of immigrants,” then we have to admit that we are, in every imaginable way, a nation of anchor babies.

Photos Courtesy of the Library of Congress – LC-USZ62-95433 and LC-USF34- 016898-C and

Map via CIS

Leave a Reply