Hurricane Harvey and its torrential flooding rains have shocked the nation. Thousands have been rescued and many more thousands have lost their homes. It is a disaster of unprecedented proportions. Hurricane Harvey and the flooding across Houston is a historic event, but it also underlines Americans’ conflicted history with our relationship to nature.

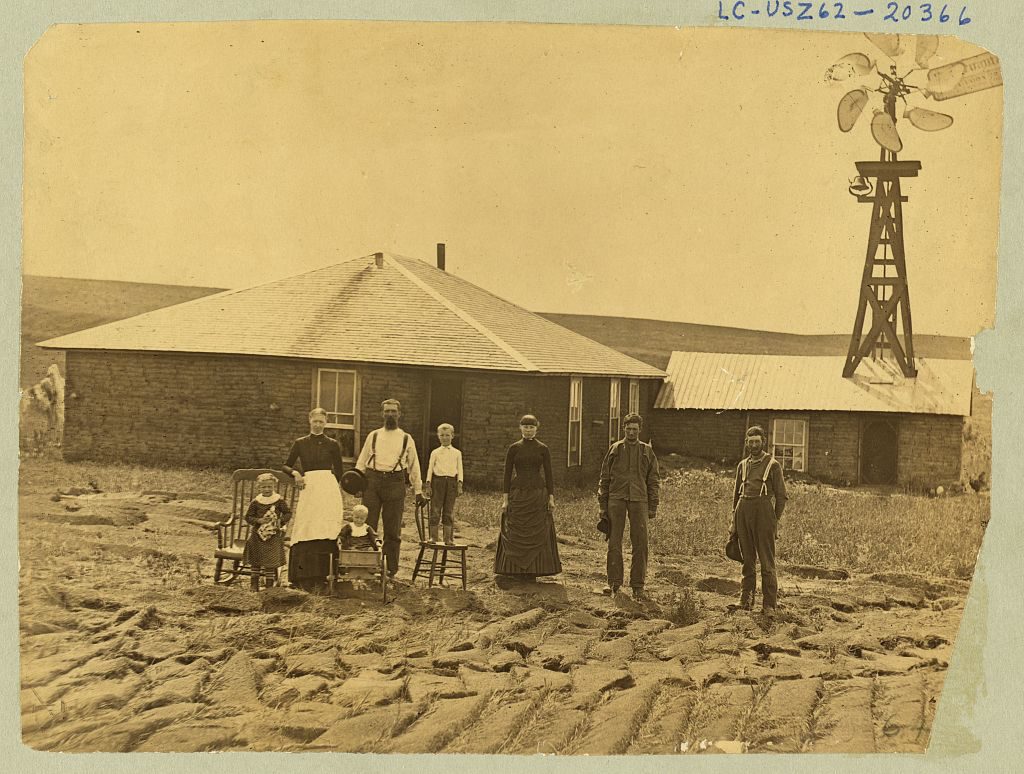

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, economic transformation and a changing way of life brought the idea of nature to the fore of public concerns. Fewer and fewer Americans lived in nature or lived the way their grandparents had just decades before. Small independent farms were declining and more and more people were working in industrial factories. In 1890, the superintendent of the Census declared the frontier in the U.S. closed. No longer was there a wilderness to dominate. By 1920, over half of Americans lived in cities. What did this mean for the nation?

For leading public intellectuals and politicians alike, the closing of the frontier and the spreading of American civilization was both inevitable and troubling. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner was concerned by the developments and in 1893 called the frontier the most significant feature of American history. It was the frontier that made the nation unique and had forged the national character. Out in the wilderness, men (the masculinist language was intentional) had tried and tested themselves against the forces of nature. Some died, but those who emerged victorious had, through their strength of will and character, dominated and defeated nature. According to Turner, that history gave America its character. It was the frontier that had made the national exceptional.

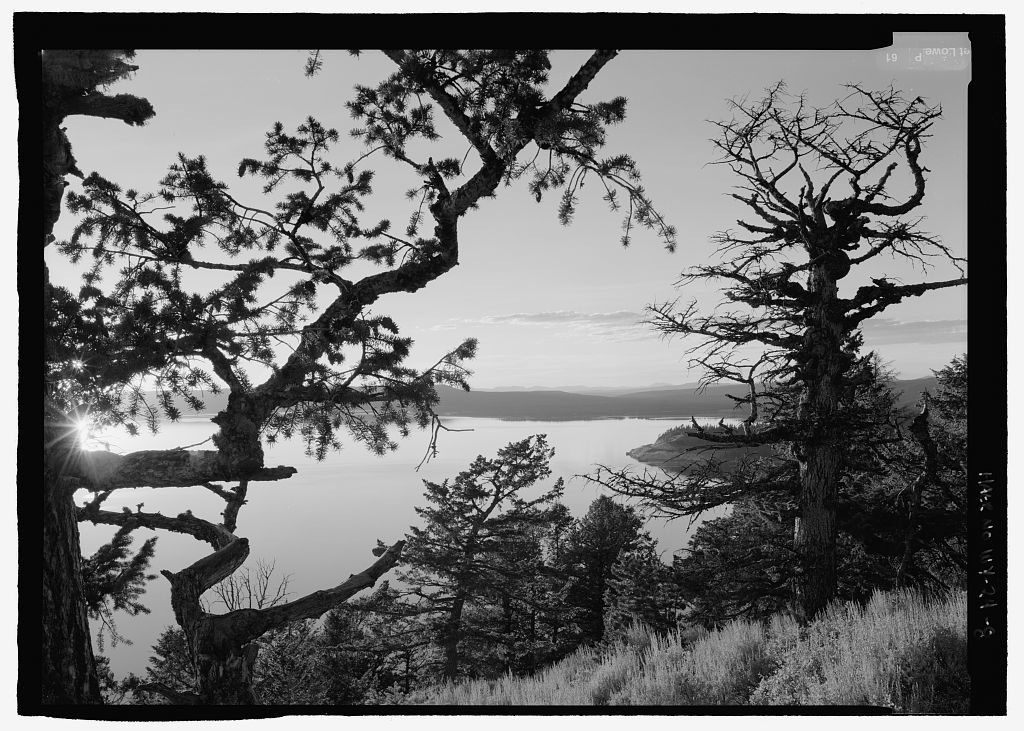

Theodore Roosevelt was also concerned about the developments that were transforming the way that most Americans lived. He was torn, because he believed in Americans’ superiority over other peoples and others way of life. Americans’ domination of the land and people was natural, but Roosevelt was concerned that Americans’ had been too successful in establishing civilization. American men, especially, were becoming too civilized. The characteristics that men learned in the wilderness that Turner so celebrated were being lost on the college educated sophisticates that dominated elite urban centers. Roosevelt worried that when American men were called upon to conquer other parts of the world, they would not be able to. His solution was for men to re-enter nature. They needed to camp, ride horses, fight, swim, and do all manner of things outside. Nature could once again hone the dull edges of American masculinity. However, as industrialization and capitalism spread across the country, establishing city after city, the wild, unkempt, outdoor spaces that would be needed for Americans to rediscover what he called the “barbarian virtues,” were being destroyed. Without some sort of intervention, Americans would lose the places where they could rediscover nature. Roosevelt’s solution was the creation of more national parks and forests. These wild spaces would be kept pristine for generations of Americans to rediscover the wilderness of the world and the wilderness inside of themselves.

Roosevelt’s efforts were aided by a growing group of activists who shared his concerns about the natural environment, but differed in their beliefs of how it should be used. For centuries, Americans had looked at nature as a limitless source of natural resources. Water, trees, minerals were unending and would be discovered as the frontier moved westward. By the end of the century, the frontier was closed and the second industrial revolution was consuming huge amounts of natural resources. The forests that so many Americans had taken for granted for so long were on the verge of exhaustion. The waters that so many depended upon were facing threats too. In the cities, industrial waste and human sewage was dumped into water supplies. At the turn of the century, only 1 in 10 Americans drank filtered water. In the west, where aridity was a fact of life, the competing interests of cities and farmers were on display. Would irrigation for farms or aqueducts for cities take precedence? Nature’s bounty, which the nation had relied upon and taken for granted for much of its history, was running out.

What could be done?

For some, the answer was to leave nature as it was, to concede that humans were just one part of the environment and had overstepped their bounds. Nature need not serve man, but man was part of nature. In fact, humans’ problems were tied to their attempts to live artificially in manufactured landscapes and environs of their making, like cities and skyscrapers. In their efforts to destroy nature, humans were willingly destroying their own freedom. The profits of nature’s bounty were not worth the price to be paid. John Muir, perhaps the most widely known philosopher, conservationist, and activist of the time, held this view. He wrote in 1901:

Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away; and if they could, they would still be destroyed — chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides, branching horns, or magnificent bole backbones. Few that fell trees plant them; nor would planting avail much towards getting back anything like the noble primeval forests. … It took more than three thousand years to make some of the trees in these Western woods — trees that are still standing in perfect strength and beauty, waving and singing in the mighty forests of the Sierra. Through all the wonderful, eventful centuries … God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods; but he cannot save them from fools — only Uncle Sam can do that.

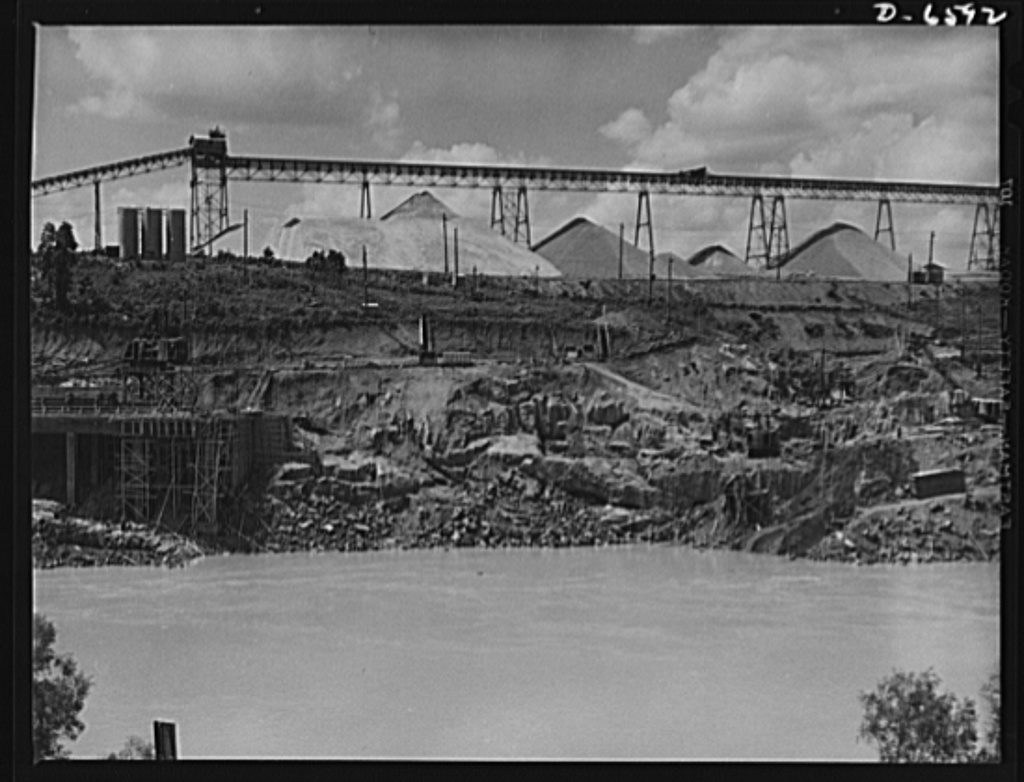

Yet, a young nation growing in wealth, power, and people was not willing to concede economic growth to environmental protection. Indeed, some believed that both could be achieved. People like Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Forest Service, believed that humans could and should manage nature. Pinchot was in charge of managing the nation’s timber and forests on national land. His decisions struck a fine line between environmental conservation and economic sustainability. Robert Underwood Johnson explained this sentiment: “human life is more sacred than scenery.” People like Pinchot believed that nature had to be managed.

And, why not? By the end of the 19th century, many progressives were more than convinced that they could manage nature because humans had freed themselves from the confines and inconveniences that nature required. Humans had mastered nature through scientific advancement and technology. The railroads had collapsed time and space. What used to take months to travel, now took weeks. What used to take weeks, now took days. Days became hours. Americans had shrunk the world. At the same time, humans had freed themselves from the grip of gravity, erecting buildings that scraped the sky with their stature and built machines that flew them into the heavens, higher than even birds. With the advent of refrigerated air and the air conditioner, they could even control the climate. These natural titans—the sun, wind, fire, water, and even time—who had controlled the destiny of so many were tamed over the course of a few decades. The concerns of nature then could not be left to effete esthetes or strange ascetics who roamed the wildernesses writing in their journals.

And try they did. The 20th century saw multitudes of federal, state, and local bureaucrats combined with private developers who were convinced of their mastery of science to control natural forces. But many misunderstood the forces they were trying to control. The attempt of the National Forest Service to suppress wildfires over the course of the 20th century only brought larger, more destructive, and more frequent wild fires that consumed property and cost many lives. The eradication of wolves changed landscapes and ecosystems in ways unimaginable. Dams flooded valleys, allowing for greater urban sprawl but changed the natural landscape. Irrigation changed dry parched earth in the west into fertile farms, but used more groundwater and river water than was replaceable. Many rivers in the west ran dry before they ever touched the ocean. The eradication of native plant species, the drying up of water sources, and the plating of non-native crops that needed huge amounts of water, not to mention the cities that depended on those farms for food, made drought even worse.

Today, we live in the world made by the previous century. Many of their projects still stand. The environmental transformation caused by many of the project of the 20th century did not stop because Americans learned from their mistakes. Instead, the funding for large infrastructural projects ran out. There was a political change not a change of heart; Americans no longer wanted to pay taxes for such expensive endeavors. So, the nation made do with what it already had. (For example, the two reservoirs made to help Houston deal with flooding, Barker and Addicks were built three-quarters of a century ago.) Yet, development did not stop. Instead, cities grew larger and larger. The U.S. has only become more urban.

Environmental historians and environmental activists will point out that all natural disasters are manmade disasters. There is nothing natural about a metroplex that contains more than 6 million humans. The homes that we live in, the cars that we drive, the air conditions we use to inhabit the inhospitable territory, the reservoirs we build (for context, every lake in Texas with the exception of Lake Caddo, on the Texas-Louisiana border is manmade), and the global supply chains we pull upon to feed the millions are all artificial. There was no natural force that attracted all these people to Houston en masse, or any other major city. Governmental policy, both local and national, economic development, tax policy, developers, corporations, and a host of other issues created a sprawling location.

“A landscape…is not just a place, it is a story,” an environmental historian wrote about the irrigation projects of Idaho, but he meant it to apply to the whole nation. It is a story that we tell ourselves about progress, about control, about our future, and about who we are as a nation. As the flood waters rose, regular people ventured out in boats, risking their lives, to save others. Many believed it was the city of Houston’s finest moment. As the flood waters recede, rebuilding has already begun. Many believe it is an example of the indomitable American spirit. It seems that we have concluded, much like Johnson almost a century ago, that human life is more valuable than scenery, but we must not forget that we are, whether parasitically or symbiotically, tethered to that scenery and it is changing under our feet and over our heads.

Leave a Reply