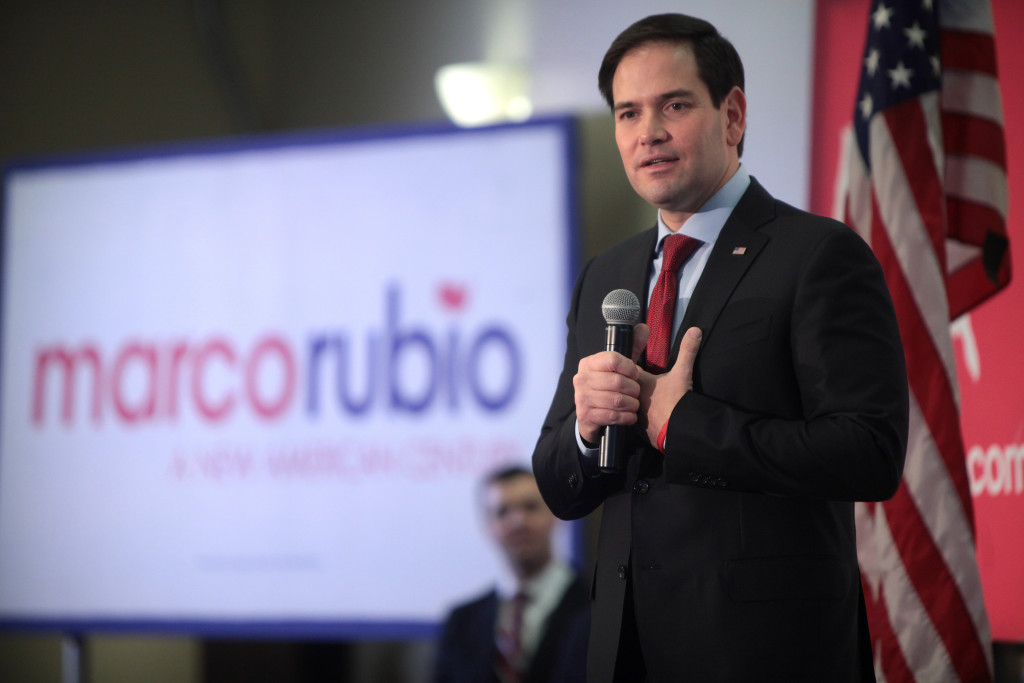

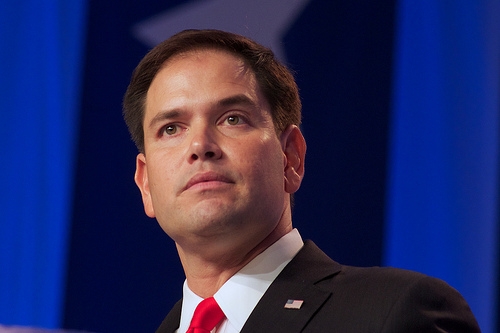

On March 15, 2016 after a devastating primary loss in his home state of Florida, Marco Rubio suspended his campaign. He won only one county, Miami-Dade. He was utterly bested by Donald Trump. His loss could very well mark the end of his career. He will lose his seat in the senate and the Florida primary revealed his limited electability at the state level. His defeat and subsequent retreat doesn’t mean he should be forgotten. Rubio, more than any other figure in the Republican Party, explains how the GOP understands the Latino community. Rubio was not a happenstance shooting-star, the wish of a wayward party come to life. His rise was certainly meteoric but this meant that he was destined for a crash-course and an eventual burn-out. His rise was always connected to his fall. Rubio’s place in the Republican Party was predicated on the fundamental misunderstandings of the Latino community by the party itself.

Keeping Things Up-to-Date

Readers, thank you for all your support. I have not posted in a while, but only because recently I have had great opportunities to publish with NPR’s LatinoUSA and LatinoRebels.com.

Back on February 17, 2016, I explained the bizarre exchange between Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz. Rubio managed to get under Cruz’s skin with a comment about Cruz not speaking Spanish. Cruz, an award-winning debater, broke character and engaged Rubio. The exchange between two Cuban-Americans trying to explain who was more draconian in their immigration policies in Spanish was the collision of two competing strands in the GOP. I outlined this for NPR’s LatinoUSA. You can read the story here.

On March 7, 2016, I examined the New Yorker’s recent coverage of Latinos in U.S. politics for LatinoRebels.com. While the New Yorker has covered many issues in Latin America and has also featured Latin American authors, it has struggled with its U.S.-Latina/o coverage. While the writing was good–the signature style of the magazine–the framing was rough and uneven. You can read “The Talk of the Brown” here.

On March 14, 2016 for NPR’s LatinoUSA, I explained why the eighth Democratic debate was a historic event. For two hours that evening the seismic shift in American culture was on display and the debate was at its epicenter. Latinos tried to turn their social presence into political power that night. The debate showed that “English Only” was not a realistic policy or possibility. For two hours, Latinos showed their adeptness at linguistic and cultural code-switching. For two hours, Latinos turned Spanish into the official language of American politics. You can read my analysis of the cultural and historical importance of the debate here.

I will continue to blog right here and will continue to publish with these top-notch outlets. Keep checking-in for more commentary and cuentos.

Part II of a History of Latino Conservatism: The Rise of Latino Neoliberalism

As covered in part I, Latino conservatism is not an outlier or a historical aberration. Many of its features developed over the course of the early twentieth century and were, at first, fused to civil right goals. Civil rights social conservatism accepted the idea that racial and economic inequality was not the product of structural problems, but individual failings. For these middle-class mid-20th century Latinos, Anglos did not systematically exclude Latinos, nor did they make Latinos poor. Instead, Latinos kept themselves in poor economic conditions and in segregated neighborhoods because they refused to assimilate, learn English, become educated, and be industrious with their time and money. Groups like LULAC and the American GI Forum subscribed to these types of ideas for much of their histories.

History of Latino Conservatism (Part I)

The coming presidential election has brought Latinos into the spotlight. Primarily, Democratic presidential hopefuls have reached out to the community, hiring key immigration activists and political actors. Yet, it is the Republican Party that has brought forward two Latino presidential candidates, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. But how did a party known most recently for its anti-immigrant stance produce the first two Latino presidential candidates? Many have wondered about how Latinos could be conservatives or if Latino conservatism is an oxymoron. United Farm Worker Union (UFW) co-founder Dolores Huerta even called them “sellouts,” a term with a long history associated with elected Latino officials. Luis Valdez, founder of Teatro Campesino, a Chicano theater troupe associated with the UFW, wrote a 1967 play called “Los Vendidos” aimed at Mexican-American appointees of Ronald Reagan, who was then governor of California.

More recently, the Republican autopsy after the 2012 elections pinpointed Latino voters as key to Republican electoral success, yet Republicans in general have only doubled-down on anti-immigrant and anti-Latino rhetoric. Citizen militias, 2nd Amendment activists, and Tea Party activists supported the rhetoric of politicians that targeted Latinos and immigrants as the source of American political and social decline. Almost all on the far right, and increasingly in the mainstream, believed that immigrants were destroying American culture. And yet, Rubio and Cruz came to the fore. Does this mark the beginning of a new era of Latino conservatism or is this an anomaly?

It is probably a little of both. Latino conservatism is not an aberration. It has a long history within the Latino community in the U.S. and it continues today. Interestingly, in many moments in history it has even intersected with civil rights activism. It is important to note, that there are many types of conservatism and not all of them have strong traditions in the Latino community.

Trump and the Tragicomedy of American Politics

Presidential hopeful Donald Trump is slated to host Saturday Night Live and Latino groups across the country have organized to protest the show. For those who want SNL to rescind the offer, Trump is the symbol of a resurgent and unapologetic nativism and racism that is directly aimed at Latinos. The show’s uneven history with diversity also points to the problematic issue of representation and white privilege. The fact that a show which refuses to acknowledge its own institutionalized racism is joining forces with a personality who is quite comfortable with his public bigotry highlights the built-in nature of racialized power in this nation. It is the institutional equivalent of the statement, “I’m not racist but…”

Trump’s appearance on SNL is not inconsequential. Comedy has, in many ways, replaced journalism as the primary institution that keeps politics honest. Today, journalists that ask difficult questions are forced out of press rooms and criticized by their peers for being “activists.” Satire like The Daily Show, Colbert Report, The Nightly Show, and Last Week Tonight have revealed nightly news shows and newsclips to be absurdist performances that operate outside of the confines of truth or policy. It is a dangerous moment when comedians are more interested in uncovering the truth and journalists are reduced to framing an unmoored “story.” What happens when our politics become performance? Trump happens.

Of Immigrants and Anchor Babies

Despite dire warnings from the Republican National Committee, a slew of Republican presidential hopefuls have veered to the right and have alienated Latino voters. In an attempt to win an aging, isolated constituency that is increasingly afraid of technological, economic, social, and demographic change, the candidates have become enamored with the idea of overturning birthright citizenship in this country.

The lesser candidates have followed front-runner Donald Trump’s nativist and xenophobic rhetoric while Floridians Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush have shown moderation, which is not surprising given their family histories. Rubio is the son of Cuban exiles and Bush’s wife was a Mexican national, which would in a very real way make Rubio and Bush’s children—including George P. Bush, Commissioner of the Texas General Land Office—anchor babies themselves. Interestingly, Jeb Bush used the term anchor baby and in a testy exchange with reporters refused to concede that the term was offensive. He pushed the media to develop a better term but ultimately concluded that “I think that people born in this country ought to be American citizens.” Rubio answered Bush’s urging to develop a better term by calling them “human beings with stories” and not just statistics.

What Do We Mean When We Talk About Assimilation?

On July 22, 2015 Republican presidential hopeful Bobby Jindal posted a petition demanding that Obama fire the director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigrations Services, Leon Rodriguez. At the top of this petition was a quote from Jindal explaining why, as a son of an immigrant, he was angry that the Obama administration would alter the oath of allegiance that would not require naturalizing citizens to militarily defend the nation:

Becoming a United States citizen is not a right, it is a privilege. Immigration without assimilation is not immigration, it is invasion. Legal immigration by people who vow to defend the United States of America can make us stronger, and my own family is evidence of this.

Then, two weeks later Jindal repeated the same phrase. He added:

We must insist on assimilation. Immigration without assimilation is an invasion. We need to tell folks who want to come here come here legally. Learn English, adopt our values, roll up your sleeves and get to work. I’m tired of the hyphenated Americans and the division. I’ve got the backbone, I’ve got the band width, I’ve got the experience to get us through this.

Jindal is deftly but also deafly conflating a myriad of matters meant to strike key issues important to the aging Republican base. At its opening, the statement is a condemnation of “illegal immigrants,” who in his estimation fail to respect the authority and appreciate the magnanimity of the U.S. Then he makes the key connections for a constituency anxious about their position in a changing economy and demographically different U.S. Immigration is supposed to be about assimilation for Republicans. If an immigrant does not “become American” then that person is infiltrating not only the nation but the culture—immigrants are invaders. Since many of these voters have a racialized understanding of immigrants, all Latinas/os are seen as immigrants, regardless if they were born in the U.S. or not. By the very presence of Latinos, Jindal’s constituency believes that they are under a verifiable invasion. Because of the invasion, the borders need to be secured. A secure border requires militarization. Militarization of the border is a defense of this nation and underlines the need to serve in the military. In his statement, Jindal wraps up a series of bumper-sticker slogans—“support our troops,” “secure the border,” “America love it or leave”—and legitimizes them through his own immigrant past.

The Republicans’ Latino Problem

Republicans’ have a Latino problem. Their anti-Mexican rhetoric isn’t working out. Donald Trump has been dumped by NBC, UNIVISION, and Macy’s for his anti-Mexican statements. Their commentators haven’t helped much either. Some have indicated that this is due to Latinos growing economic and political influence. Nonetheless, the ever-growing Republican presidential field features the first two Latino presidential candidates in U.S. history, Texas senator Ted Cruz and Florida Senator Marco Rubio. Both are Cuban and both espouse a particular brand of American exceptionalism and anti-federal government policy solutions.

When they tell their families’ stories, however, they are not aimed at Latina/o families. Instead, their immigrant narrative is a repetition of an idealized nineteenth century story that does not fit into the late twentieth century context in which it unraveled. In their recounting, their families seem more like German or Italian families than the Cuban diaspora. Their families never passed by the Statue of Liberty or entered Ellis Island, but they came to the U.S. for the American dream, for the chance to succeed and experience a type of freedom unequaled anywhere in the world. At first their families were poor, oppressed, and downtrodden but they worked hard and sacrificed. Then, they succeeded—both economically and in assimilating. The only particularity of the Cuban experience that Cruz and Rubio mention is that their families fled communism. For them, communism—of which American liberalism is just a step away, brought closer by Obama’s near Marxism—is any form of government intervention. Big government, whether Castro’s communism or Roosevelt’s New Deal—robbed their families of opportunity, oppressed their communities, and sapped individual initiative. Their families and community witnessed the horrors of government run amok and that’s why they don’t want to see it in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave. That’s why they are anti-liberal crusaders—they’ve seen the destruction that liberalism can bring.

Donald Trump’s Delusional Free Market

Donald Trump announced his presidential run on a strange anti-Mexican platform to great applause. In an hour long, rambling speech Trump laid out various explanations for American social, political, and economic decline. The problem with America: Mexican rapists and bad (political) cheerleaders. If it wasn’t for evil, violent Mexicans and Obama, the U.S. would be as strong as it (n)ever was.

Trump’s announcement was longwinded and incoherent. The only semi-constant theme through the speech is that government is inefficient and the market is efficient. This is a tried-and-true slogan of the Reagan Revolution; namely, that the freer the markets the freer the people and that government is the problem, not the solution. In fact, politics and politicians will only continue to hurt the nation. There are no quick policy fixes, but there is a great white hope: Trump himself. He’s a billionaire, a businessmen, and a red-blooded American. By his own bootstraps, but mainly his $9 billion billfold, he’ll rebuild America and put it back to work.