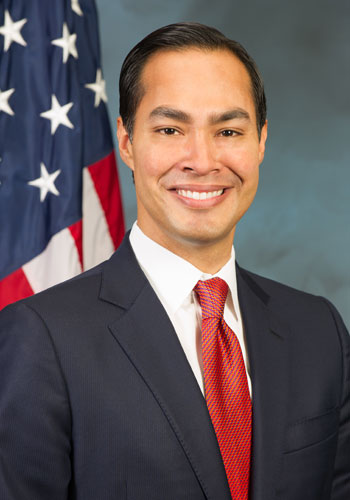

On October 15, 2015, the last day of Hispanic Heritage Month, Hillary Clinton flew to San Antonio to receive a key endorsement from HUD secretary and rising-star in the Democratic Party, Julian Castro. Clinton played Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and spoke Spanish, not much better than a former Democratic presidential hopeful’s wife nearly 55 years ago. Castro is probably the most prominent Latino politician in the nation, coming out of Texas with its important electoral votes and changing demography. But other than the fact that a popular Latino politician in the Obama administration endorsed “La Hillary,” why does this matter?

José and Jorge: Latino News and Latinos in the News

It is no longer surprising to find Latinos in the news. Fluctuating demographics and Republican rhetoric regularly bring attention to the fact that Latinos are part of a changing nation. It is rare, however, to find Latino newsmen as the topic of headlines. Recently, the two of the highest-profile Latino newsmen have made the news themselves—José Díaz-Balart and Jorge Ramos. Díaz-Balart’s MSNBC show, The Rundown, is set for cancellation as the network makes more room for Joe Scarborough’s Morning Joe. Ramos garnered immediate attention for his exchange with Donald Trump in Iowa, where he was forcefully removed and told to “go back to Univision.” Later, in the hallway, a Trump supporter would tell Ramos to “get out of my country.” Ramos, a U.S. citizen, tried to explain that he was in his country, but the supporter refused to acknowledge that fact.

The coverage of the exchange moved away from Ramos’ engaged insistence that politicians tackle immigration reform, toward Ramos himself. Terry Gross had Ramos on Fresh Air, where he acknowledged she would not have him as a guest if it was not for the episode. The New Yorker wrote a feature on him, calling him “The Man Who Wouldn’t Sit Down.” The altercation even garnered international attention, acclaimed Mexican journalist, Carmen Aristegui, commented that “[Ramos] is controversial and some think that he is too aggressive, but I think he is a valuable journalist.”

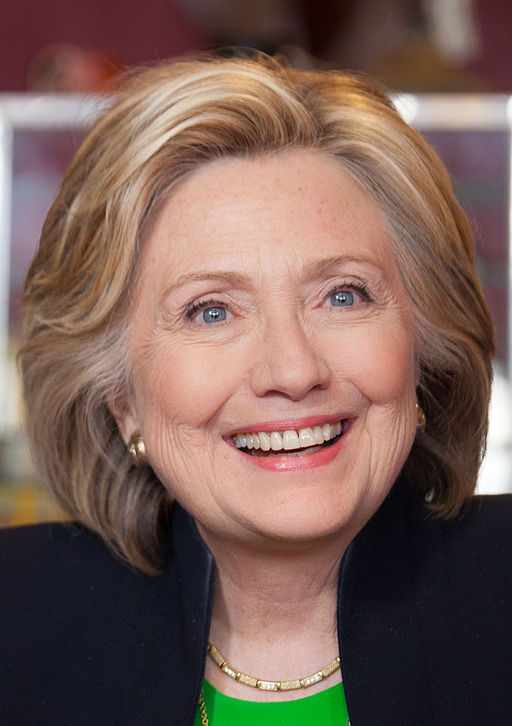

Hillary’s Stand With Latinos

Hillary stands with Latinos, apparently. She wrote an op-ed declaring her solidarity with Latinas/os and she tweets in Spanish.

But, there is still a problem with Hillary’s message. Her historicity is unmoored which allows for the creation of a happier, rosier, kinder story of the nation. Instead of delving into the complicated, controversial American past, she provides an exceptionalist vision of America that is misremembered to explain why America has been great, why America is great, and why America will be great in the future. She writes:

Will we continue to be a country that is proud of our immigrant heritage? That continues to welcome the struggling, the striving, and the successful to our shores? That continues to offer unparalleled opportunities and freedoms to all? Or will we make among the biggest mistakes we could by turning our backs on the world and allowing hatred to turn into policy?

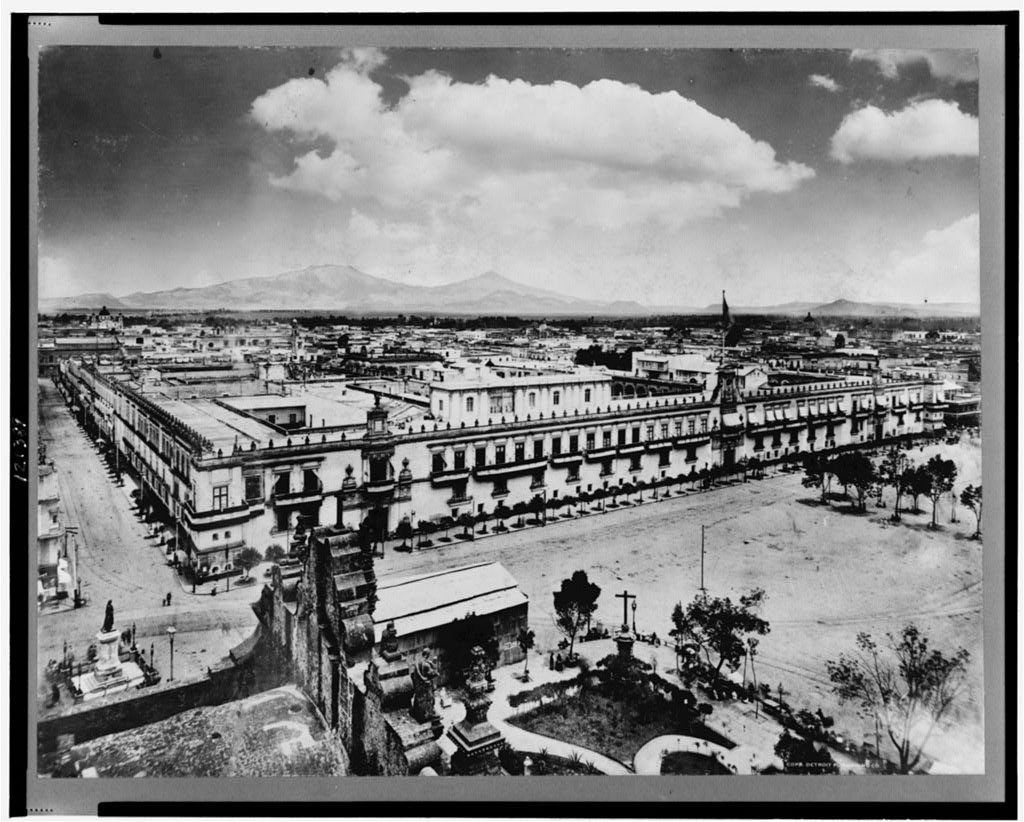

México Emigrado y México Esclavo

Mexico celebrated its 205th year of independence with the traditional grito. Yet, on the 16 of September 2015, some wonder whether Mexico has anything to celebrate, whether the people of the nation are independent or free. Under the current president, Ernesto Peña Nieto, politically-expedient disappearances have increased in the nation. In the case of the forty-three disappeared school teachers, multiple mass grave sites were found—none of which held the bodies of the teachers and instead brought to light the murder of so many unknown and unnamed people. Drug violence continues, political corruption is endemic, and popular political disaffection continues to spread. Political disenchantment on Independence Day is common, a day that begs for introspection and remembrance. On the same day in 1918 a Mexican journalist, suffering from the same disillusionment wrote, “the 16th of September… will be a day of pain; for the inhabitants of the biggest cities of Mexico it will be a day of desecration.” He continued, “This is not the time to sing, nor the time to give in to vain laments. We must prepare to return to our land; we will restore profaned altars; we will recover our country.”

Interestingly, the author of the article was not writing from Mexico City, or the industrial cities of the North. He was writing from San Antonio, Texas. He was part of an elite exile class living in the United States, displaced by the radicalism and violence of the Mexican Revolution. Of course, journalists and rich businessmen were not the only ones who fled to the U.S., both then and now. Millions of Mexicans made their way northward and between 1920 and 1930 the ethnic Mexican population in the U.S. grew over 100 percent.

Of Immigrants and Anchor Babies

Despite dire warnings from the Republican National Committee, a slew of Republican presidential hopefuls have veered to the right and have alienated Latino voters. In an attempt to win an aging, isolated constituency that is increasingly afraid of technological, economic, social, and demographic change, the candidates have become enamored with the idea of overturning birthright citizenship in this country.

The lesser candidates have followed front-runner Donald Trump’s nativist and xenophobic rhetoric while Floridians Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush have shown moderation, which is not surprising given their family histories. Rubio is the son of Cuban exiles and Bush’s wife was a Mexican national, which would in a very real way make Rubio and Bush’s children—including George P. Bush, Commissioner of the Texas General Land Office—anchor babies themselves. Interestingly, Jeb Bush used the term anchor baby and in a testy exchange with reporters refused to concede that the term was offensive. He pushed the media to develop a better term but ultimately concluded that “I think that people born in this country ought to be American citizens.” Rubio answered Bush’s urging to develop a better term by calling them “human beings with stories” and not just statistics.

The Neoliberal Arts and Chicana/o Studies

William Deresiewicz’s incisive cover story in the August issue of Harper’s, “The Neoliberal Arts: How College Sold its Soul to the Market,” criticizes higher education for its misshapen form and circumspect goals at the beginning of the twenty-first century. According to Deresiewicz, this is the age of neoliberalism, an era and an ideology that reduces all values, skills, and thought to its monetary value. “The worth of a thing is the price of the thing. The worth of a person is the wealth of a person,” he writes.

William Deresiewicz’s incisive cover story in the August issue of Harper’s, “The Neoliberal Arts: How College Sold its Soul to the Market,” criticizes higher education for its misshapen form and circumspect goals at the beginning of the twenty-first century. According to Deresiewicz, this is the age of neoliberalism, an era and an ideology that reduces all values, skills, and thought to its monetary value. “The worth of a thing is the price of the thing. The worth of a person is the wealth of a person,” he writes.

This is not a new critique. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, capitalism has certainly produced its fair share of discontents. Marx wrote of the alienated working class reduced to nothing but the value of their labor sold on the market. Henry David Thoreau wrote of the “mass of men who lead lives of quiet desperation” as the industrial revolution eliminated the singularity of homespun products and replaced them with standardization and mass production. If all products and parts were undifferentiated and interchangeable, so too were the people. Critiques of this kind would continue through the New Left and Generation X, but are limited among the millennial generation—a generation that seems to have made peace with capitalism.

What Do We Mean When We Talk About Assimilation?

On July 22, 2015 Republican presidential hopeful Bobby Jindal posted a petition demanding that Obama fire the director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigrations Services, Leon Rodriguez. At the top of this petition was a quote from Jindal explaining why, as a son of an immigrant, he was angry that the Obama administration would alter the oath of allegiance that would not require naturalizing citizens to militarily defend the nation:

Becoming a United States citizen is not a right, it is a privilege. Immigration without assimilation is not immigration, it is invasion. Legal immigration by people who vow to defend the United States of America can make us stronger, and my own family is evidence of this.

Then, two weeks later Jindal repeated the same phrase. He added:

We must insist on assimilation. Immigration without assimilation is an invasion. We need to tell folks who want to come here come here legally. Learn English, adopt our values, roll up your sleeves and get to work. I’m tired of the hyphenated Americans and the division. I’ve got the backbone, I’ve got the band width, I’ve got the experience to get us through this.

Jindal is deftly but also deafly conflating a myriad of matters meant to strike key issues important to the aging Republican base. At its opening, the statement is a condemnation of “illegal immigrants,” who in his estimation fail to respect the authority and appreciate the magnanimity of the U.S. Then he makes the key connections for a constituency anxious about their position in a changing economy and demographically different U.S. Immigration is supposed to be about assimilation for Republicans. If an immigrant does not “become American” then that person is infiltrating not only the nation but the culture—immigrants are invaders. Since many of these voters have a racialized understanding of immigrants, all Latinas/os are seen as immigrants, regardless if they were born in the U.S. or not. By the very presence of Latinos, Jindal’s constituency believes that they are under a verifiable invasion. Because of the invasion, the borders need to be secured. A secure border requires militarization. Militarization of the border is a defense of this nation and underlines the need to serve in the military. In his statement, Jindal wraps up a series of bumper-sticker slogans—“support our troops,” “secure the border,” “America love it or leave”—and legitimizes them through his own immigrant past.

Jon Stewart and the Legacy of the New Left

Jon Stewart is leaving his post at the Daily Show after sixteen years. Rolling Stone wished goodbye to him as the “last honest newsman.” He was one of the few people who kept both the media and politicians honest. The Daily Show and Stewart rose to prominence in an era when Americans had very little faith in news and politicians. He leaves a vacuum in American satire, commentary, and politics but also leaves a legacy in form of the shows hosted by Larry Wilmore and John Oliver.

While he leaves his own legacy, Stewart is part of a longer tradition of the New Left. The New Left came about in the 1960s and 1970s. They were young college students upset with the Vietnam War, inspired by the Civil Rights movements across the country, and made comfortable by the plenty of the post-WWII economy. The New Left set itself apart from the old left of the 1920s and 1930s. The old left was a political tradition worried about the inherent inequality of the capitalist system, focused on the need to organize workers on the shop floor, and tried to resist the efforts of a global bourgeoisie. The New Left was not interested in the Marxist alienation from the means of production, instead their alienation was personal. They were disenchanted and disaffected. They felt themselves empty and sought a truer form of authenticity.

In American Politics, Se Habla Español

Latinos are receiving increasing attention in American politics. Candidates and their campaigns must decide how best to reach out to this growing community. Trump has chosen to double-down on anti-Mexican rhetoric, but other candidates have chosen another language altogether. Democrats and Republicans alike have chosen to address Latinas/os in Spanish. Hillary Clinton tweeted how to say “Go Hillary in Spanish.” With an obvious slant toward a Mexican dialect, the first option was “Oralé Hillary.” She has also been criticized for her facebook post of three pictures with the caption “¡Cómo pasa el tiempo!” Her post came on a Thursday, participating in “throwback Thursday” or “#retrojueves.” Her use of Spanish was seen as a crass grab at instead of meaningful outreach to the Latina/o community.

Between Paleoliberalism and Neoliberalism: Latinos’ Past and Future

Judging by the changing prefixes—paleo, neo, new paleo—it would seem that American liberalism is in flux. In her most recent and most touted economic address, Hillary Clinton has returned to the liberal belief in government intervention, probably pushed there by Bernie Sanders. Her speech has received attention but not necessarily celebration. She has been criticized for not addressing income inequality with redistribution policies. In a very smart essay, Matthew Yglesias called Clinton a “new paleoliberal.” That is, she has revived some very important beliefs of a pre-Reagan era that saw its highpoint between 1963-1968 in the LBJ administration. Namely, Clinton believes that government can be part of the solution and the market has been part of the larger problem of increasing economic inequality in the post-1970s U.S. David Brooks of the New York Times wrote that Clinton’s belief in government solutions was “epistemologically naïve” and politically unwise. Brooks reasons that voters no longer believe that the government can solve the big problems the nation is facing. This is true, in part. Americans’ optimism in the government has waned since the 1970s, with cynicism spread by both the left and the right.

Clinton’s renewed optimism in government backed solutions to systemic problems is important for the Latina/o community because in a poll conducted for UNIVISION Noticias she leads the presidential pack in the Latino community. Clinton would receive 64 percent of the general Latino vote, while the closest Republican hopeful, Jeb Bush, would only receive 27 percent. Among Latino Democrats, she has 73% of the vote, while her contenders are largely unknown (68 percent did not know or had not formed an opinion of Bernie Sanders and 74 percent did not know or had not formed an opinion of Martin O’Malley).