As covered in part I, Latino conservatism is not an outlier or a historical aberration. Many of its features developed over the course of the early twentieth century and were, at first, fused to civil right goals. Civil rights social conservatism accepted the idea that racial and economic inequality was not the product of structural problems, but individual failings. For these middle-class mid-20th century Latinos, Anglos did not systematically exclude Latinos, nor did they make Latinos poor. Instead, Latinos kept themselves in poor economic conditions and in segregated neighborhoods because they refused to assimilate, learn English, become educated, and be industrious with their time and money. Groups like LULAC and the American GI Forum subscribed to these types of ideas for much of their histories.

History of Latino Conservatism (Part I)

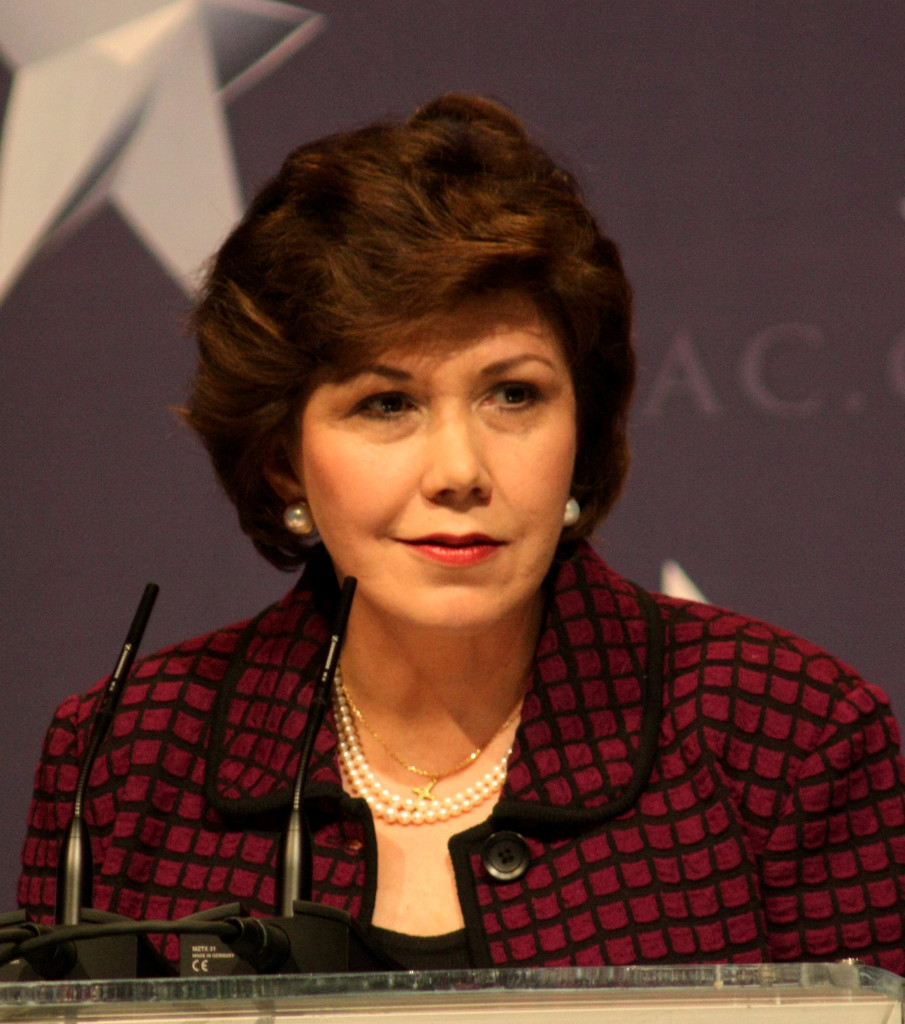

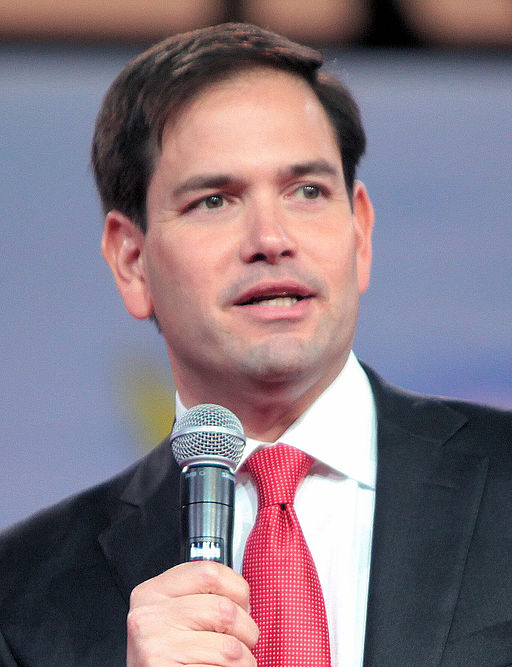

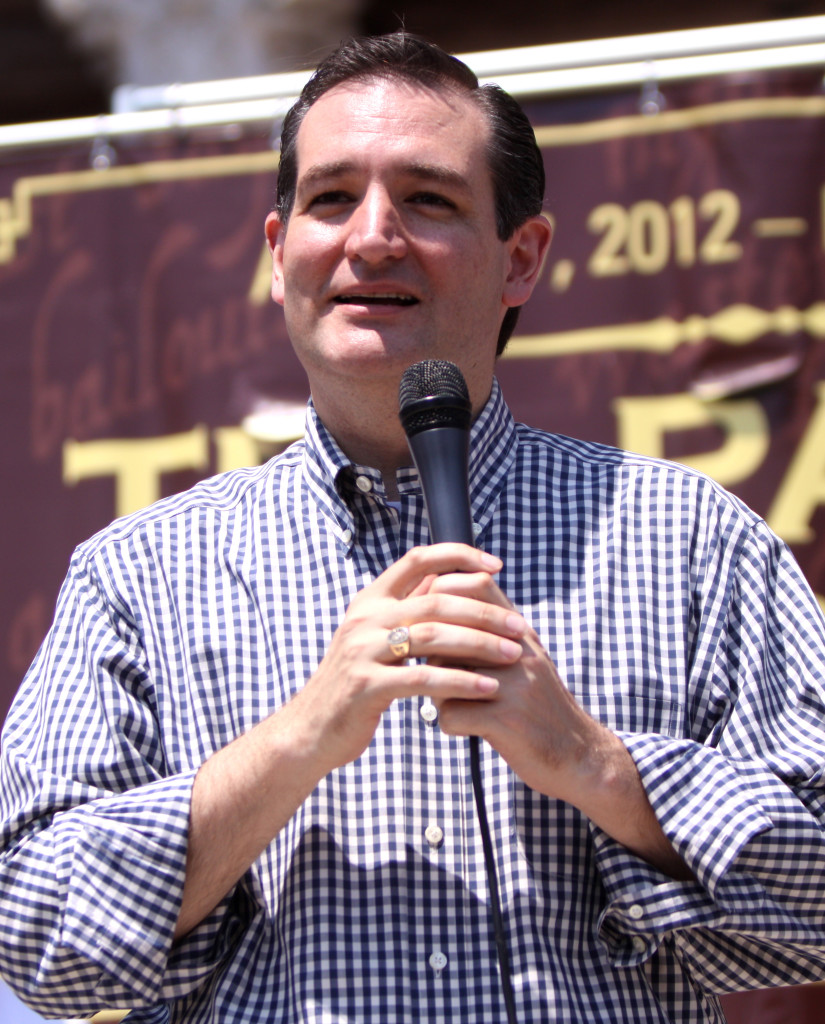

The coming presidential election has brought Latinos into the spotlight. Primarily, Democratic presidential hopefuls have reached out to the community, hiring key immigration activists and political actors. Yet, it is the Republican Party that has brought forward two Latino presidential candidates, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. But how did a party known most recently for its anti-immigrant stance produce the first two Latino presidential candidates? Many have wondered about how Latinos could be conservatives or if Latino conservatism is an oxymoron. United Farm Worker Union (UFW) co-founder Dolores Huerta even called them “sellouts,” a term with a long history associated with elected Latino officials. Luis Valdez, founder of Teatro Campesino, a Chicano theater troupe associated with the UFW, wrote a 1967 play called “Los Vendidos” aimed at Mexican-American appointees of Ronald Reagan, who was then governor of California.

More recently, the Republican autopsy after the 2012 elections pinpointed Latino voters as key to Republican electoral success, yet Republicans in general have only doubled-down on anti-immigrant and anti-Latino rhetoric. Citizen militias, 2nd Amendment activists, and Tea Party activists supported the rhetoric of politicians that targeted Latinos and immigrants as the source of American political and social decline. Almost all on the far right, and increasingly in the mainstream, believed that immigrants were destroying American culture. And yet, Rubio and Cruz came to the fore. Does this mark the beginning of a new era of Latino conservatism or is this an anomaly?

It is probably a little of both. Latino conservatism is not an aberration. It has a long history within the Latino community in the U.S. and it continues today. Interestingly, in many moments in history it has even intersected with civil rights activism. It is important to note, that there are many types of conservatism and not all of them have strong traditions in the Latino community.

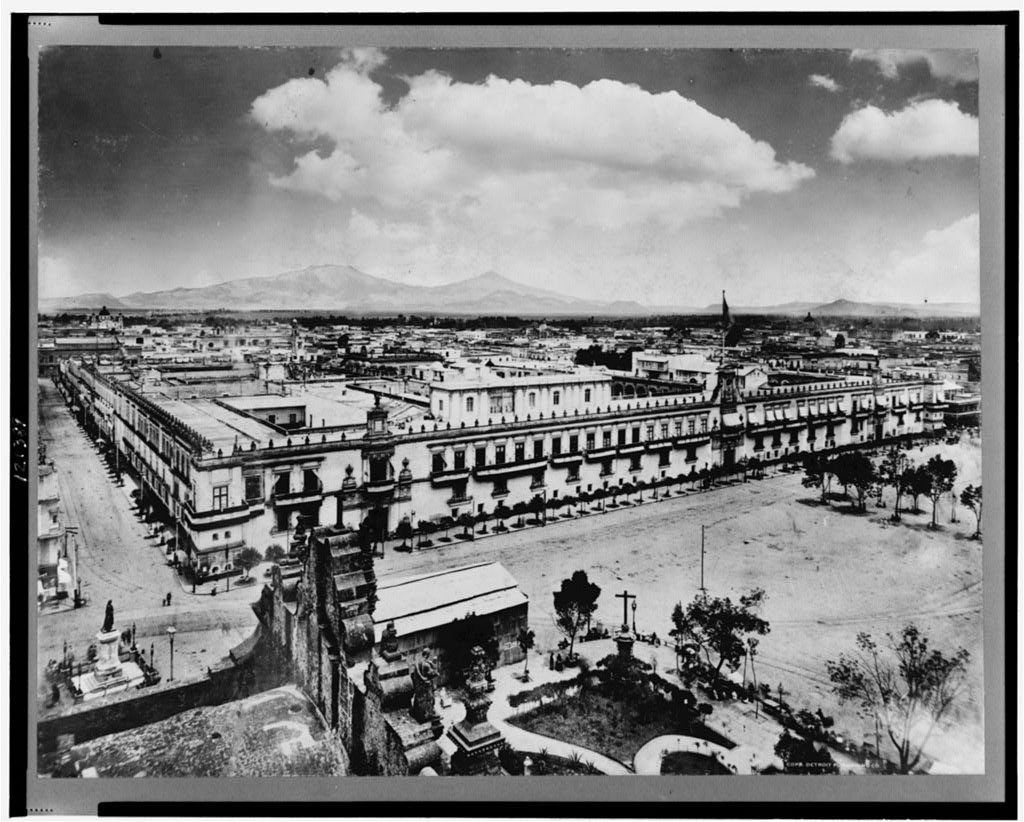

México Emigrado y México Esclavo

Mexico celebrated its 205th year of independence with the traditional grito. Yet, on the 16 of September 2015, some wonder whether Mexico has anything to celebrate, whether the people of the nation are independent or free. Under the current president, Ernesto Peña Nieto, politically-expedient disappearances have increased in the nation. In the case of the forty-three disappeared school teachers, multiple mass grave sites were found—none of which held the bodies of the teachers and instead brought to light the murder of so many unknown and unnamed people. Drug violence continues, political corruption is endemic, and popular political disaffection continues to spread. Political disenchantment on Independence Day is common, a day that begs for introspection and remembrance. On the same day in 1918 a Mexican journalist, suffering from the same disillusionment wrote, “the 16th of September… will be a day of pain; for the inhabitants of the biggest cities of Mexico it will be a day of desecration.” He continued, “This is not the time to sing, nor the time to give in to vain laments. We must prepare to return to our land; we will restore profaned altars; we will recover our country.”

Interestingly, the author of the article was not writing from Mexico City, or the industrial cities of the North. He was writing from San Antonio, Texas. He was part of an elite exile class living in the United States, displaced by the radicalism and violence of the Mexican Revolution. Of course, journalists and rich businessmen were not the only ones who fled to the U.S., both then and now. Millions of Mexicans made their way northward and between 1920 and 1930 the ethnic Mexican population in the U.S. grew over 100 percent.