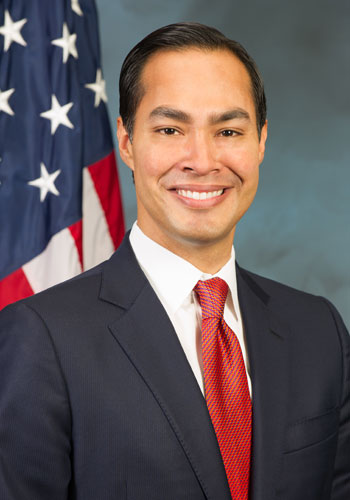

On October 15, 2015, the last day of Hispanic Heritage Month, Hillary Clinton flew to San Antonio to receive a key endorsement from HUD secretary and rising-star in the Democratic Party, Julian Castro. Clinton played Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and spoke Spanish, not much better than a former Democratic presidential hopeful’s wife nearly 55 years ago. Castro is probably the most prominent Latino politician in the nation, coming out of Texas with its important electoral votes and changing demography. But other than the fact that a popular Latino politician in the Obama administration endorsed “La Hillary,” why does this matter?

Impact on Latino Politics

It is not new that Democratic presidential hopefuls seek key Latino endorsements. The most salient early example of this dates back to 1959, with the Viva Kennedy campaigns across the Southwest. Mexican-American support for the Kennedy-Johnson ticket essentially won them Texas and, subsequently, the nation. Key politicians like Henry B. Gonzalez, Albert Peña, and Hector P. Garcia believed that by supporting the Democratic ticket, Latinos would be rewarded with influential appointments. They did not. Only El Paso mayor, Raymond Telles, was given an ambassadorship.

Some Latinos learned their lessons from the disenchantment of the Viva Kennedy campaign. Peña formed a more activist political organization called the Political Association of Spanish Speaking Organizations (PASO) in 1962. By 1970, Chicana and Chicano activists in Texas formed La Raza Unida Party (LRUP, the United People’s Party) as a way to gain political clout. PASO and LRUP declined by the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, as their members left to join the Democratic Party. Through the ‘80s and ‘90s, Democrats paraded Latinos around when they felt they needed support from the Latino community. Yet, Latinos were absent from any substantive policy role or leadership position. The endorsements mainstream Democrats sought from Latinos were obvious window-dressing.

What has changed in the 21st century is that these endorsements are no longer obvious pandering. Half of Democratic Party voters are non-white. A Latino turns 18 every 30 seconds in the country. The U.S. is now the second largest Spanish-speaking nation in the world, second only to Mexico. By 2050, Latinos will compose nearly a quarter of the population. For these reasons, politicians need Latinos, not for pandering purposes, but for electoral power. Latinos will be at the table, they will be in the room when decisions are made. Not many of them, but a few at least.

In addition, key Latino endorsements will be important because the Democratic Party still needs intermediaries to speak to the Latino Community. Even the Republican Party no longer needs political translators. Rubio and Bush can speak directly to Latinos—not only in Spanish but to their experiences as Latinos in the U.S. or being part of intercultural Mexican and American families—even though Latinos don’t care much for their policies. It was not lost on many viewers of the recent Democratic debates that the stage was unrepresentative of Democratic voters. The candidates were from east of the Mississippi. Few of them have any substantive experience with the Latino community. If Latino politicians are not the candidates themselves, they will serve as the arbiters for Democratic candidates, cultural and political bridge-builders between the chasm of the Southwest and the Northeast. They will be both the go-betweens and go-tos of the Democratic Party.

Impact on Latino Politicians

While Latino politicians are being sought after for their endorsements, their tenuous positions at the state and national level are of concern. Take Castro for example. Castro is undeniably popular among Latinos in Texas and across the Southwest. As mayor of San Antonio he was celebrated and well respected. He was tapped by the Obama administration as the secretary for Housing and Urban Development. Yet, Castro left Texas because he had no chance of state-wide office. Not only because he was Latino, but because no Democrat in the state of Texas holds state-wide office. Castro left Texas because he had nowhere to go beyond San Anotnio. His political career, at that moment, had no future in Texas.

Castro’s HUD appointment provided him a national stage and Castro’s endorsement of Clinton is yet another smart political calculation. Democrats certainly need Latinos, but for Castro, he needs national Democratic support and, more importantly, Democratic donors. Clinton provides Castro access to that world. Whether she wins or loses, Castro comes out on top. Bernie Sanders cannot provide Castro with the donors or the mainstream Democratic connections that Clinton can because he is running as an “outsider.” Castro most likely wouldn’t “Feel the Bern,” but would be burned with Sanders.

Castro’s example, if successful, could be a model for other Latino politicians from Southwestern states that must deal with strong Republican presence at the state level. Latino politicians from states like Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and Texas could be plucked from lower-level offices and this could help propel them to the national stage.

Impact on Latinos

Castro’s endorsement does not change Clinton’s policy positions. In that way, Castro’s endorsement has a minor impact on Latinos if her policies do not already reflect the issues important to the Latino community. Clinton has promised to maintain President Obama’s executive actions on immigration and she promises to go further. She has promised to support the DREAM act. She wants to lower the interest rate on student loans and provide paid maternity leave. She would like to minimize the income gap between men and women. These programs will have an impact on Latinos. As a self-proclaimed “Progressive that likes to get things done,” Clinton will be more than willing to compromise in order to win the passage of key legislation.

Sanders’ main issue, income inequality, without an overt emphasis on Latinos, will also have an impact on them. The concentration of wealth among fewer families and the erosion of the middle-class are of concern for immigrant and working-class Latino families who aspire to climb the social ladder. Hard work and education—two foundational tenets of promised American prosperity—will not suffice in an increasingly bifurcated economy and society.

For these reasons, it is crucial that Latinos pay attention to the issues and to the policies, not just the promises and endorsements.

Leave a Reply