In Berkeley, CA in 1964, Free Speech Movement leader Mario Savio decried the old institutions of social change had been compromised. Unions, universities, the government, all had been bureaucratized, which meant in the langue of their time, sterilized, scrubbed clean, and removed of their humanity. Liberalism had failed them; in the quest for systematic reform the engine of social changed and stalled and become a monstrous machine instead.

The time for radical change, possibly revolution, had come. It was time to destroy, to sacrifice all in an effort to make the uncaring machinations end. Savio passionately urged his fellow students:

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, make you so sick at heart that you can’t take part! Put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon the apparatus—and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got ot indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it—that unless you’re free the machine will be prevented from working at all!

It was not just the white college students who voiced a general frustration with American society and politics. Young Chicanas, Chicanos, Native-Americans, and African-Americans all voiced their anger over government failure to address the problems that affected them. In the decades since the Great Depression, Americans had turned to the government as the main institution to provide them protection from a wildly fluctuating economic system that they were almost all universally dependent upon but had no control over individually. The state, through mindfully managed macroeconomic planning and social programs, would provide regular workers and citizens a certain level of security. But as the decades wore on, it seemed that the promises of liberalism and the proposed economic solutions were not reaching minority communities.

In 1960, for example, only 13% of Mexican-Americans had a high school education and less than 6% attended college. Nearly 40 percent of Mexican-Americans across the country were living below the poverty line. In La Salle County, in South Texas, the median number of school years completed was only 1.4 grades. After decades of liberal programs and the beginning of the War on Poverty, Chicanas, Chicanos, and other Latinos began to think that the institutions were not broken, but were working exactly as they were supposed to.

In a now infamous 1969 speech, Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and La Raza Unida Party founder José Angel Gutiérrez told the press, “MAYO has found that both federal and religious programs aimed at social change do not meet the needs of the Mexicanos of this state….[Gringo] institutions not only severely damage our human dignity but also make it impossible for La Raza to develop its right of self-determination….Our organization, largely comprised of youth, is committed to effecting meaningful social change. Social change that will enable La Raza to become masters of their destiny, owners of their resources, both human and natural, and a culturally and spiritually separate people from the gringo.”

Across the nation in New York City the Young Lords Party (YLP) was using similar language in identifying the failures of the key institutions in American society. In the YLP “13 Point Program and Platform,” the party explained in points 4 and 5,

The Latin, Black, Indian and Asian people inside the u.s. are colonies fighting for liberation. We know that washington, wall street, and city hall will try to make our nationalism into racism; but Puerto Ricans are of all colors and we resist racism…..We want control of our communities by our people and programs to guarantee that all institutions serve the needs of our people. People’s control of police, health services, churches, schools, housing, transportation and welfare are needed.

Increasingly, these young activists took aim at the liberal politicians and programs that were supposed to help them out of poverty. The liberal politicians were just as much a part of the problem. Chicana poet Angela De Hoyos described Mexican-American politicians in 1974 as people who were

(lost in a ticker-tape mountain / of mundane ideas: / love-thine-enemy policies / hypocritical handshakes / social-science amenities / and e pluribus unum) / a formula infallible for painless living.

Community organizer and poet, Ricardo Sanchez, described Mexican-American politicians as “A.S.S.[es],” meaning middle-class Americans of Spanish Surname who used their last names opportunistically to enrich themselves and feed their hunger for self-importance. One of the most scathing critiques came from Luis Valdez’s 1967 acto “Los Vendidos.” In the short play, he sardonically describes a Mexican-American politician as the “apex of American engineering! He is bilingual, college educated, ambitious!” The generic Mexican-American politician then gives a sample pre-programmed speech outlining the problems of the Mexican-American community:

I come before you as a Mexican-American to tell you about the problems of the Mexican. The problems of the Mexican stem from one thing and one thing only: He’s stupid. He’s uneducated. He needs to stay in school. He needs to be ambitious, forward-looking, harder-working. He needs to think American.

As the title suggests, many considered Latino liberal politicians mere sellouts who bought into the cultural deficiency theories that explained racial inequality as the product of deficient minority cultures of poverty. It was clear for the youth: the system was flawed and the politicians were bought.

Throughout the long decade of the ‘60s there were many reasons to question the motives of the liberal establishment. Increased intervention in Vietnam, FBI suppression of the Civil Rights Movement, the scandal of Watergate, and a long decade of economic decline in the ‘70s, eroded the trust in the liberal policy solutions. Faith eroded among both the political left and right.

Today we find ourselves in yet another season of discontent. Both the left and the right have blamed the “establishment” for the problems that are plaguing society. The populist message is clear: the economy is rigged, regular people are losing their social standing, the government is either complicit in corporate malfeasance or the cause of it, banks are reaping all the rewards of risky investments but none of the costs. For many across the country the foundational structures of American society are broken. On the right, this has produced Donald Trump and the humiliating defeat of three heavily touted Republican governors (Bush, Kasich, and Christie). On the left, the establishment backlash has been levied at Hillary Clinton, but also Latino progressives like Julían Castro, Tom Perez, and Dolores Huerta. While “establishment” has been hurled as an insult, its meaning is unclear. In many cases, it means those people and politicians that have been in charge for long amounts of time, whose opinions are heard, influence felt, and are responsible for government policy. The distrust of longtime politicians correlates with the half-century long decline in government trust.

In 1958, under the liberal consensus and the Eisenhower administration, 73% of Americans trusted the government. In 1964, one the eve of the more radical beginnings of the ‘60s, 74% of nonpartisan leaning voters, 80% of Democratic leaning voters, and 74% of Republican leaning voters trusted the government. By June of 1976, those numbers had eroded across the board and across the nation. Only 29% of nonpartisans, 36% of Democrats, and 36% of Republicans trusted the government. Vietnam, the shooting of students at Kent State, and Watergate caused many to rethink their connection to government. Those numbers only continued to decline throughout the century. In 2015, Pew Research Center found that only 16% of nonpartisans, 26% of Democrats, and 11% of Republicans trust government, nearly all-time lows. Interestingly, Latinos tend to trust government more than Whites and African Americans. Although the statistics have only been tracked since 1988, Latinos trust in government peaked under the Clinton administration, reaching nearly 60%–even after a series of policies that would devastate the Latino community which included NAFTA, the 1994 Crime Bill, and the 1996 immigration act. Today, over 30% of Latinos trust the government but less than 20% of Whites do.

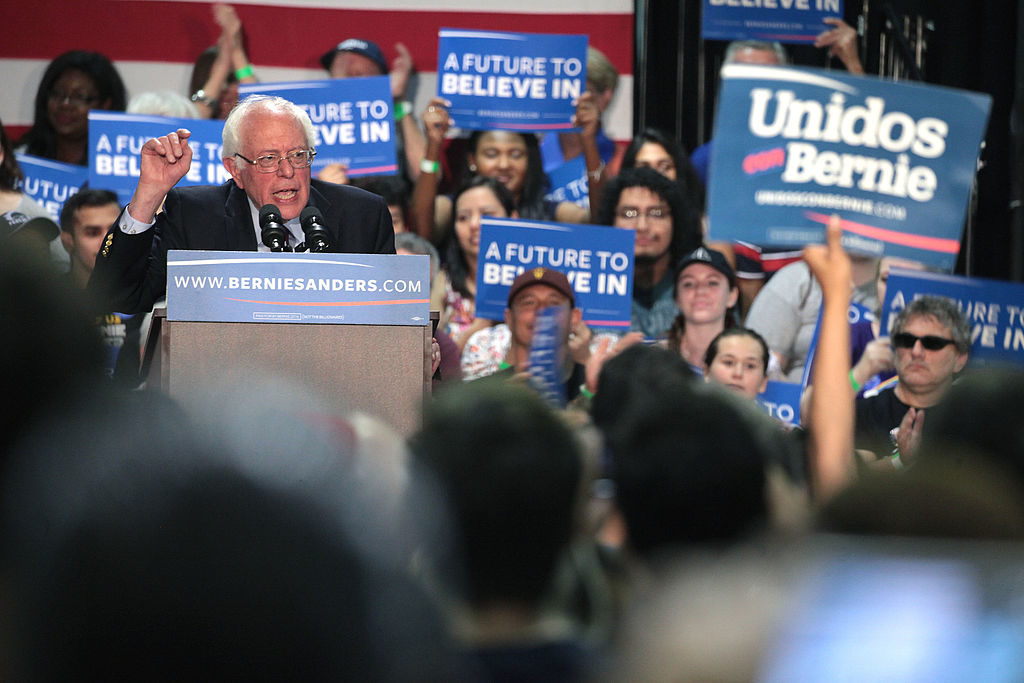

Latino Millennials are playing a key role in the refiguring of American and Latino politics. Millennials in general are the largest generation in the U.S. today and Latino millennials comprise nearly half of all U.S.-Latino voters in the nation. Millennial politics have been shaped profoundly by the fallouts and backslides in American politics and economics since the Civil Rights Movement. They are wary of major social institutions like organized religions, mainstream media, and large corporations. Yet they hold high regard for small businesses and technology companies. Forged in midst of the Neoliberal era, their politics and outlooks favor an individualism that is both easily coopted by doctrinaire capitalist self-interest and seeks to avoid their personal erasure into greedy corporations and faceless bureaucracies. The political establishment that they speak of embodies all of these characteristics. As Latino millennials have turned their attention to this election, they have overwhelmingly supported Bernie Sanders. Clinton has struggled among young voters in general and especially with young minority voters.

Their critique of not only Democratic politics but of Latino politicians is telling. On the other hand, the overwhelming support of Latino politicians for Clinton is revealing as well. The younger generation explains the schism between the populations and the community similarly as Chicanas and Chicanos did. Latino politicians must be vendidos, sellouts. They are corrupted and self-interested. They are brainwashed and dehumanized. Some, especially Republican Latinos, are called self-hating agringados.

Today, Latinos have a similar outlook regarding the liberal establishment as they did during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. Yet, today we need a political language that goes beyond the vendido and blind veneration.

The Chicano Movement, the New Left, the Civil Rights Movement, urged us to be conscious of the political establishment, wary of it, concerned by it. In the messy aftermath of the long decade of the Civil Rights Movement, we have a culturally cool anti-establishment sentiment on the left—one that was celebrated through rock music in the ’70s, punk in the ’80s, and even the Daily Show and the Onion in the 2000s—and a politically paranoid anti-government outlook on the right—one promulgated out of the racist anxieties of whites after the gains of the Civil Rights Movement by Republicans and cultivated throughout the century until they voted Trump. On the left, this has been especially troubling.

Students for a Democratic Society, and most of the groups of the New Left, wanted a “participatory democracy” because they felt that the levers that controlled their fates were too far out of their reach. Their destinies were out of their hands. For those reasons the entirety of the machine needed to be brought down, so the machinations of authority would be destroyed. Today, do we need our bodies on the machines? Latino liberals want to place their hands on the levers and change the direction of the machine. The younger generation is once again saying the machine has taken on a life of its own, while the lives of average Latinos are left uncared for. The critique of the “establishment” is telling. It reflects a reality of uncertainty and pessimism. It reflects a belief that an institution or organization, regardless of the insecurities of the future, will outlive us all. Its future is more certain, more secure, than our own.

Photo of Grape Boycott and Bernie Sanders via Wiki Commons

Leave a Reply