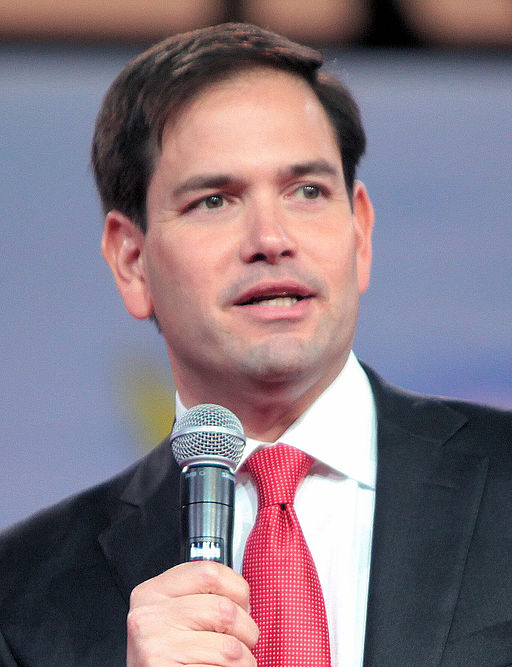

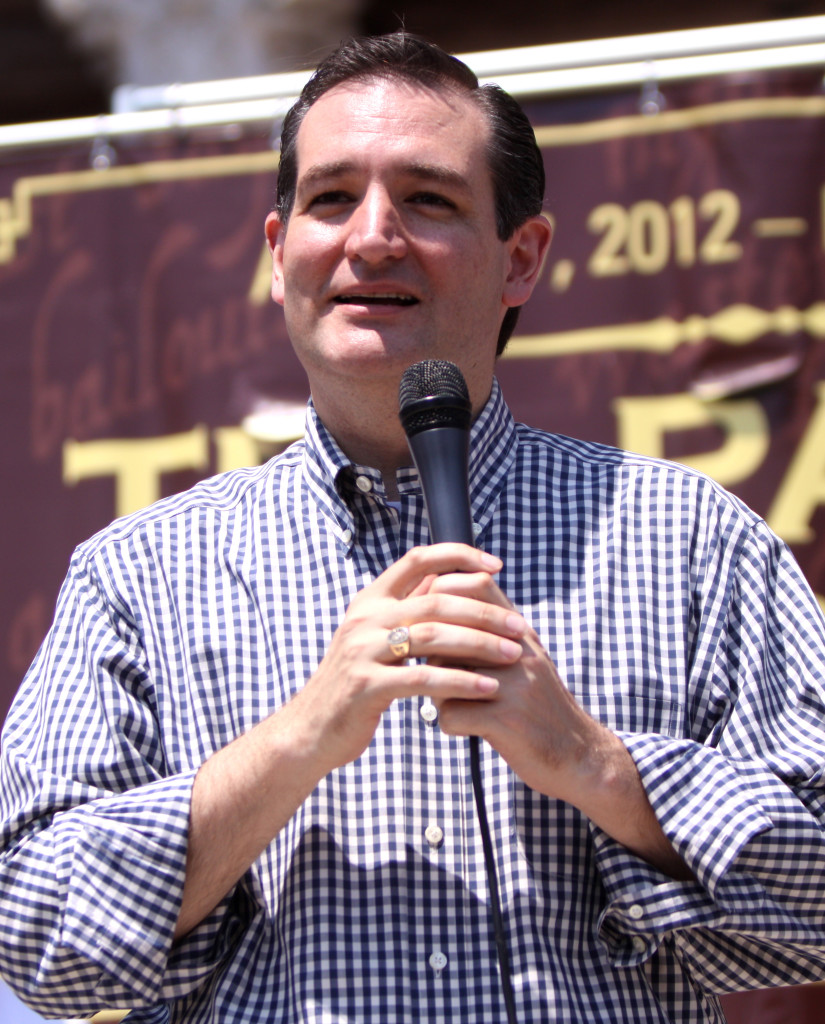

The coming presidential election has brought Latinos into the spotlight. Primarily, Democratic presidential hopefuls have reached out to the community, hiring key immigration activists and political actors. Yet, it is the Republican Party that has brought forward two Latino presidential candidates, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. But how did a party known most recently for its anti-immigrant stance produce the first two Latino presidential candidates? Many have wondered about how Latinos could be conservatives or if Latino conservatism is an oxymoron. United Farm Worker Union (UFW) co-founder Dolores Huerta even called them “sellouts,” a term with a long history associated with elected Latino officials. Luis Valdez, founder of Teatro Campesino, a Chicano theater troupe associated with the UFW, wrote a 1967 play called “Los Vendidos” aimed at Mexican-American appointees of Ronald Reagan, who was then governor of California.

More recently, the Republican autopsy after the 2012 elections pinpointed Latino voters as key to Republican electoral success, yet Republicans in general have only doubled-down on anti-immigrant and anti-Latino rhetoric. Citizen militias, 2nd Amendment activists, and Tea Party activists supported the rhetoric of politicians that targeted Latinos and immigrants as the source of American political and social decline. Almost all on the far right, and increasingly in the mainstream, believed that immigrants were destroying American culture. And yet, Rubio and Cruz came to the fore. Does this mark the beginning of a new era of Latino conservatism or is this an anomaly?

It is probably a little of both. Latino conservatism is not an aberration. It has a long history within the Latino community in the U.S. and it continues today. Interestingly, in many moments in history it has even intersected with civil rights activism. It is important to note, that there are many types of conservatism and not all of them have strong traditions in the Latino community.

The myriad strains of conservatism are on display in the Republican primary. In one telling exchange between Rubio and Rand Paul in the third primary debate, Paul blasted Rubio for his support of government instituted family tax credits. He demanded to know how government intervention was conservatism, pushing Rubio to define his brand conservatism. For Paul, true conservatism was not only small government but anti-statist. That is, the less government the better and no government is the best. This libertarian strain of conservatism is a strange mixture. It is a blend of Jeffersonian republicanism, a belief that economically independent small producers are self-governing and politically independent making government redundant; Austrian school economics, a group of economists that believed contra-Keynes that government intervention in the economy imbalanced the naturally self-regulating, self-equilibrating nature of the free market and that government would lead to the road to serfdom; radical individualism, a belief that posits that individuals seeking their own self-interests promotes the best social outcomes; and Friedman-esque libertarianism, the idea that free-markets have inherently emancipatory powers and potentials that bind freedom to capitalism. All of these are tied into a neat post-Reagan neoliberal package. The bridging of pre-industrial and post-industrial political economy gives this package of ideas a veneer of historicity, a faux constitutional originalism that hides its ideological contradictions as “tradition.”

But, for the majority of the 20th century, the most influential strain of conservatism in the Latino community was a dramatically different one. It was a social conservatism, wrapped in the modernist and cultural deficiency theories of the mid-century that explained the causes of racial and economic inequality as the behaviors and actions of the minority communities themselves and not racism or the failures of capitalism. The origin of the Latino community’s inequality was the community’s own personal and moral failings, not any larger shortcomings of the social or economic structures. The responsibility for their shortcomings, then, was squarely on their shoulders. This reasoning prevailed through the20th century and persisted with a few updates into the 21st century.

The mixing of activism and social conservatism began as early as the mid-19th century in the Southwest. Many of the anti-colonial uprisings in the Southwest after 1848 that pushed back against Anglo incursion were wrapped in the privileges of sexism. The ideas of the Enlightenment, Mexican liberalism, and American republicanism rooted natural rights in the bodies of men. Men, not women, were entitled to life, liberty, and private property (or as Jefferson wrote “the pursuit of happiness”). Under 19th century ideas, men were entitled to respect because of property ownership and men were responsible for guiding society and politics. Men like Juan Cortina, Catarino Garza, and Joaquin Murrieta based their claims for equal treatment on the grounds that they were men—men, equal to other men and deserving of their natural rights. Women, on the other hand, were only addressed as damsels in need of defense—a responsibility that men could not shirk. Indeed, many felt that they had been called to rebellion by their manly duties to protect their women and honor. In addition, they believed that they were responsible for letting Anglo men take their rights, an act of passivity which required violence and virility in response. While women could push men to action, they believed that women, as dependents, could and should be excluded in politics and economics. The patriarchal anti-colonialism of the late 19th century came to an end because of increasing governmental power and bureaucratic reach. But that was not the end of Latino civil rights social conservatism.

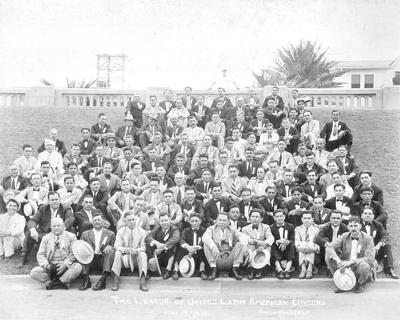

From the 1920s to the mid-1960s, middle-class Mexican-American groups dominated by middle-aged business men and men who hoped to climb the social ladder dominated the civil rights landscape. In the 1920s, they were influenced by modernist ideas and progressive politics that located the origins of Mexican-American inequality in the deficiencies of the race and culture. They identified the solution as assimilation and capitalist production.

Capitalism, for the Mexican-American middle-class progressives, was not a malevolent force. Instead, capitalist production was the avenue for Mexican-American success. By working harder, they would produce more, thus earning more. Capitalist competition, too, was a way to prove Mexican-American equality with whites. Mexican-American economic success and employment meant they were equal to or better than whites. What was holding Mexican-Americans back in this new context and contest, then, was Mexican culture itself. Mexican-Americans needed to assimilate. For example, in 1928 influential Mexican-American lawyers and soon-to-be president of LULAC wrote to then president of LULAC, Ben Garza, about his stay in Nicaragua:

Although I am an American citizen and the United States is the leading country in the world, I belong to the Mexican-American component element of our nation, and as a racial entity we Mexican-Americans have accomplished nothing that we can point to with pride. Were I to criticize Nicaraguans for their filthy and backward towns and cities, they would in all probability retort: ‘How about your Mexican villages (otherwise known as Mejiquitos) in San Antonio, Houston, Dallas, and other Texas cities and Towns?’ I believe I would have to agree with them that our Mexican districts in the United States are just as filthy and backward as Managua….What are we Mexican-Americans going to do about the matter? Are we going to continue in our backward state of the past, or [are] we going to get out of the rut, forge ahead, and keep abreast of the harddriving [sic] Anglo-saxon?

For Perales, Garza, and many early Mexican-American civil rights activists, Anglo economic success was evidence of the superiority of their ideas, education, and morals. For them, economic advancement correlated with advanced social and moral development.

It was the duty, then, of the Mexican-American middle class to lead the way. The poor needed saving, not from capitalism or racism, but from themselves. If poor ethnic Mexicans or other Latinos were ever to become middle-class, they needed to be taught to behave like the middle-class. In 1931, Manuel C. Gonzalez explained that LULAC taught the common Mexican worker to “comport himself as a gentleman…learn to economize in order that he may better his economic situation, [and] improve intellectually.” They believed that much of the discrimination ethnic Mexicans received in public was due to their poor clothes, hygiene, and manners. Once these differences were addressed, then there would be no reason for segregation.

In the early 20th century, social conservatism, capitalism, and civil rights activism intersected. Capitalism was not a system that created systematic exclusion and poverty. Instead, it provided a proving ground where individuals of Mexican descent could compete and achieve individual success. Eventually, enough individuals—with the right drive, education, and middle-class morals—would succeed. These successful people, as a collection of individuals, would help the community succeed. In their understanding, the community was not a larger collective or unit, like the proletariat, but a collection of individuals.

These ideas only grew through the two World Wars and through the uber-patriotism of the Cold War era. As the Cold War grew into the simmering stand-off between not just two economic systems but two antipodean ways of life, capitalism became equated with freedom in the United States. For many, free markets created free people. To critique capitalism then was tantamount to communism. To be anything other than 100% American, true and loyal, was somehow communist tinged. Leftists and left-liberal coalitions were pushed to the margins. The policies of the Liberal Consensus acknowledged the presence of economic and racial inequality, but eventually mindful economic growth managed by the central government in cooperation with private companies would produce social equality by making sure that everyone had a place in a responsible capitalist system. Eventually, economic growth would solve all the social problems of the United States and even the world. Mexican-American groups continued to believe that assimilation and integration in the market economy would produce Mexican-American equality and they tried to prove their unfailing American patriotism.

In 1965, the major California Mexican-American organizations (MAPA, LULAC, the CSO, and the G.I. Forum) wrote a resolution to President Johnson asking for aid. The introduction to the resolution was couched in the language of Cold War patriotism. In the resolution’s logic, U.S.-Mexicans were loyal citizens even before there was a nation and they had resisted territorial incursions into the United States by the forerunners of the communist USSR:

Over 150 years ago, Spanish-speaking Mexican-Americans stopped the Russian colonial advance and conquest from Siberia and Alaska, and preserved the Western portion of the United States for our country, which at that time consisted of thirteen colonies struggling for their existence, into which nation we and our predecessors became incorporated as loyal citizens and trustworthy participants in its democratic forms of government.

U.S.-Mexicans, then, had been fighting communism on American soil since at least the Spanish colonial period. While their chronology was flawed, their ideology was clear. Mexican-Americans were Americans by blood and by territory, even before they were Americans. With the arrival of thousands of Cuban refugees in the 1960s, anti-communism would continue to grow in influence in the creation of a national Latino politics.

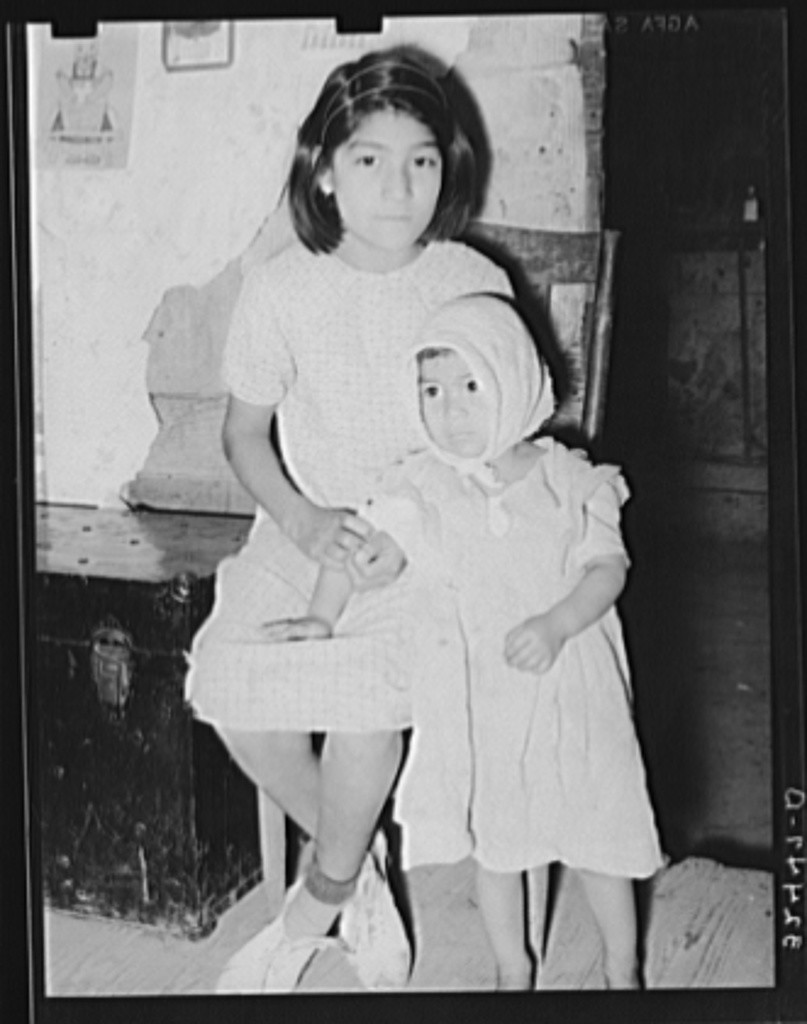

The Chicano Movement of the long decade of the ‘60s challenged many of the ideas and policies of the previous generation. From a policy standpoint, Mexican-Americans still lagged in education, income, and home ownership. In the late 1960s in Bexar County Texas, which had one of the largest Mexican-American middle-classes, average educational attainment was only 5.5 grades. In La Salle County in South Texas, the median number of school years completed was only 1.4 years. Mexican-Americans were overrepresented, however, in poverty and high school dropout rates.

These younger Chicana and Chicano activists saw these statistics as evidence of the structural flaws of American society and the economy. They began to take aim at the older cohort of elected officials, demanding them to address these structural inequalities. Eventually, young activists declared the electoral system itself as flawed and corrupt. Mexican-American politicians, then, were also corrupted; they were vendidos, or sell-outs. Their politicians had “sold-out” the Mexican-American community for fancy suits, fancy job titles, and fancy cars. Mexican-Americans politicians were complicit with white supremacy in their constant assertion for assimilation. The younger generations of Chicanos did not believe there was anything wrong with their working-class bilingualism and biculturalism.

These older politicians pushed back. They called Chicanos long-haired communists. The venerated Texas congressman from San Antonio, Henry B. Gonzalez, called activists the new “reverse racists.” Gonzalez had grown up with the civil rights social conservatism of LULAC and others. He could not believe that young Chicanos would criticize American culture and politics. He proclaimed adamantly in a 1969 speech that he “cannot accept the argument that this is an evil country or that our system does not work….I cannot find evidence that there is any country in the world that matches the progress of this one.” He would continue to lash out at young activists for their lack of patriotism and anti-war positions throughout the next decade.

Gonzalez actively tried to destroy the Chicano Movement, as well. He worked with the FBI to gather information on activists and their activities. The opposition to larger movements for civil rights, equality, and liberation pushed many Chicanos to harsher critiques of establishment Mexican-American politicians. Many increasingly saw Henry B., as he was affectionately called, as the epitome of the Mexican-American politician. He was the embodiment of the vendido, complacent with his political position and unwilling to challenge or confront the problems of inequality. One activist under the pseudonym, “la mano negro de Aztlán,” (the black hand of Aztlán) wrote a poem entitled “un canto de amor para henry b.,” accusing him of complacency and reactionary politics:

has muerto / henry b. / has muerto / and i shed no tears / for your dying. / you are dead / henry b. / you are dead / por ver traicionado / a tu Raza / eras mi hermano / henry b. / but pieces of copper / made a judas of you. / You were my brother / henry b. / you were my brother / pero prefieres ‘atole’ / a ser hombre honrado. / dormirás con gusanos / henry b. / dormirás con gusanos / in the much and the slime of / white green exploitation. / sleep with the worms / henry b. / sleep with the worms / mientras la Raza levanta / ‘su casa en el sol’ / has muerto / henry b. / has muerto / and i shed no tears by / your grave. / you are dead / henry b. / you are dead / por ver tracionado / a tu Raza. / but / i love you / henry b. / i love you. / porque en tu falsedad / has dado valor / a mi Raza, Aztlan.

By the 1970s, the linkages of civil rights social conservatism had been frayed by the activism of the younger generations. Yet, social conservatism as a force in the Latino community or in the U.S. did not diminish. Unhinged from civil rights activism and detached for its political affiliations, social conservatism sought a new home, a place where its explanation of poverty as a product of personal moral failings and cultural deficiencies was welcomed. As both Left and Right lost faith in the power of the government to be a force for good and social change and the influential social metaphors that connected Americans throughout the 20th century unraveled, a new political coalition tied free-market ideology with social conservatism.

In this new collection of ideas, the market was a perfect self-regulating, self-correcting system in which individuals competed of their own free will, evenly matched. Government intervention only disrupted the self-equilibrating features of the market. Since the system was perfect and it depended upon individual effort for success or failures, then individuals alone (not society or a “white power structure” as some activists from the ‘60s and ‘70s suggested) were responsible for their fates. Racial inequality and poverty, then, were the products of individuals’ own personal shortcomings, lack of skill, or lack of will. Government intervention only mucked up the movement toward economic equilibrium, which produced the best social outcome. So it was government intervention that caused larger problems (like unemployment and inflation) in society and the economy. In fact, government depended on dependency. The government, not the market, was a malevolent force that required poverty to foster dependency and create a perpetual need for government bureaucracies.

The forces of the New Right rose to national prominence with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. He harnessed the power of a coalition moved by disaffection, economic anxiety, and fear. He also won the support of Latino civil rights social conservatives who had always believed that individuals were responsible for their own economic situation and social advancement, but who had turned away from the civil rights movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Reagan and the New Right provided them an answer out of recession, racial inequality, and poverty: individual effort not government intervention. Reagan announced famously in his inauguration address in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” He added later, the crisis of the U.S. was not to be solved by government but by individual Americans’ “best effort and our willingness to believe in ourselves and to believe in our capacity to perform great deeds.”

The prominent strain of social conservatism of the twentieth century was then detached from civil rights activism and linked to the proposals of a new conservative politics. A new generation of Latino neoliberalism had just begun.

Photo Credit:

Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio photos via WikiCommons

1929 LULAC Convention via LULAC.org

Black and white photos courtesy of the Library of Congress: LC-USF34- 032479-D, LC-USF34-032447-D, LC-USF34-032524-D,

Leave a Reply